"After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Williston

North Dakota began to gear up for war. The

railroad yard, being a railhead for the building of the Alcan Highway, was very

busy, and there were rumors that the Japanese could drop bombs on the yard at

any time. One of the first things

that was done was to set up a civil defense organization with a head quarters,

air raid wardens, emergency medical facilities, evacuation programs, etc. there

was a call for boys of 12 to 16 years of age to act as messengers. These boys

would carry messages between headquarters and wardens, using bicycles.

A lot of this had to be done at night and it sounded very exciting.

At the appointed time I went to the headquarters building (down stairs in

the old library) to hear about and apply for the job.

I was dismayed when I found about 150 other boys

waiting there impatiently for the same purpose. It turned out that the town was divided into 10 areas with an

air raid warden for each area and block wardens as assistants, so only 12

messengers were needed. I did not

think I had a chance, but took the papers home anyway, where my mother convinced

me that “nothing ventured, nothing gained” so I filled out and sent them

off. Two weeks later, I received a

letter in the mail (about the first one I had gotten that was not from a family

member) from the board of civil defense stating that I had been appointed a

messenger. Oh joy and what fun! We

were given an armband with the messenger logo (triangular in shape, blue in

color, with a gold triangular border around a gold lightning bolt), a lapel pin

of similar design, and a white hard hat.

The first part of our training consisted of how to

putout incendiary bombs, first aid, evacuation, and communication with the

various wardens etc. No training

was given on how to ride a bike in unfamiliar territory in complete darkness,

but of course we could handle that, oh yeah!

The next part of our training was the real thing.

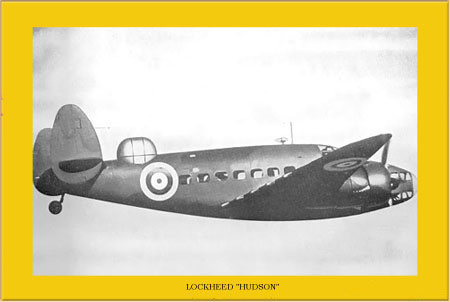

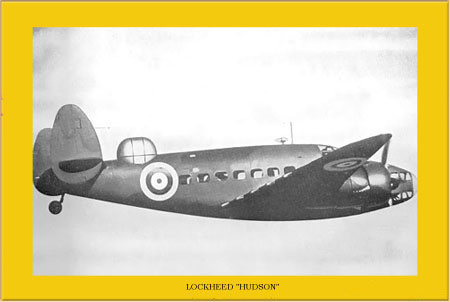

There was a Canadian airbase for Lockheed “Hudson

bombers” about 150 miles north of Williston and the airmen stationed there

needed training. This fit right in

with the plans of the civil defense people and so Williston was “bombed”

about 2 times a week, sometimes in daylight, and sometimes at night.

No one seemed to know when the attacks were scheduled, so we had our

bikes with us at all times (we even took them to school in the winter) and

“high tailed” it to headquarters when the air raid siren sounded.

Then the fun began; the planes came across town at

about 1000 feet on bombing runs in the daylight hours, and it was pretty simple

for us to deliver our messages between headquarters and air raid wardens and

between air raid wardens and block wardens.

But at night it was a different story.

The planes came across at about 200 feet in the dark, and used bright

spot lights in the nose to illuminate any speck of light they observed, if the

spot lights got you, it was reported as a casualty. The wardens all had blue lights on their porches to guide us;

evidently blue lights are hard to see from the air. We were allowed flashlights with regular lenses, but we were

admonished to only use them in extreme emergencies, which meant peddling down

unpaved and unfamiliar streets in complete darkness, as during the “raids”

the town was under “black out” conditions.

One night while wending my way down a particular bad

stretch of road, I had to use my flash light to keep from crashing (I had

skinned elbows and knees to attest to bad falls on other occasions), a bomber

swooped over me, made a short low turn and came at me head on with the spot

light at full blast. From about 100

feet up those twin radial engines made the most wonderful and awesome racket, I

can still hear them to this day. However, I knew that of the number of

casualties listed for that night, I was one of them.

Within about a year, someone realized that the

Japanese were not likely to bomb our town, and apparently the bomb crews had all

been trained. The bombing ceased,

but not before friendships had been forged between some of the girls in

Williston and some of the pilots of the bombers who made visits by automobile,

on regular occasions, during that year.

And what happened to the messengers?

We were pressed into service to collect scrap iron, newspapers and rubber

tires for the war effort throughout the county.

We had a wonderful time, as one of our number, Bob Batty, was allowed to

drive his fathers pickup on these forays. But it was nothing like being chased

in the night by bombers bent on adding you to the casualty list.