Alexander Calder , American

Alexander Calder (1898-1976), whose career spanned much of the 20th century, was the second child of artist parents—his father was a sculptor and his mother a painter. Because his father, Alexander Stirling Calder, received public commissions, the family traversed the country throughout Calder's childhood. Calder was encouraged to create, and from the age of eight he always had his own workshop wherever the family lived. For Christmas in 1909, Calder presented his parents with two of his first sculptures, a tiny dog and duck cut from a brass sheet and bent into formation. The duck is kinetic—it rocks back and forth when tapped. Even at age eleven, his facility in handling materials was apparent.

Despite his talents, Calder did not originally set out to become an artist. He instead enrolled at the Stevens Institute of Technology after high school and graduated in 1919 with an engineering degree. Calder worked for several years after graduation at various enginerring jobs until he moved to New York and enrolled at the Art Students League in 1923.

He also took a job illustrating for the National Police Gazette, which sent him to the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus to sketch circus scenes for two weeks in 1925. The circus became a lifelong interest of Calder's, and after moving to Paris in 1926, he created his Cirque Calder (video) , a complex and unique body of art. The assemblage included diminutive performers, animals, and props he had observed at the Ringling Brothers Circus. Fashioned from wire, leather, cloth, and other found materials, Cirque Calder was designed to be manipulated manually by Calder. Every piece was small enough to be packed into a large trunk, enabling the artist to carry it with him and hold performances anywhere. Its first performance was held in Paris for an audience of friends and peers, and soon Calder was presenting the circus in both Paris and New York to much success. Calder's renderings of his circus often lasted about two hours and were quite elaborate. Indeed, the Cirque Calder predated Performance Art by forty years.

He also took a job illustrating for the National Police Gazette, which sent him to the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus to sketch circus scenes for two weeks in 1925. The circus became a lifelong interest of Calder's, and after moving to Paris in 1926, he created his Cirque Calder (video) , a complex and unique body of art. The assemblage included diminutive performers, animals, and props he had observed at the Ringling Brothers Circus. Fashioned from wire, leather, cloth, and other found materials, Cirque Calder was designed to be manipulated manually by Calder. Every piece was small enough to be packed into a large trunk, enabling the artist to carry it with him and hold performances anywhere. Its first performance was held in Paris for an audience of friends and peers, and soon Calder was presenting the circus in both Paris and New York to much success. Calder's renderings of his circus often lasted about two hours and were quite elaborate. Indeed, the Cirque Calder predated Performance Art by forty years.

In October 1930, Calder visited the studio of Piet Mondrian in Paris and was deeply impressed by a wall of colored paper rectangles that Mondrian continually repositioned for compositional experiments. He recalled later in life that this experience "shocked" him toward total abstraction. For three weeks following this visit, he created solely abstract paintings, only to discover that he did indeed prefer sculpture to painting.

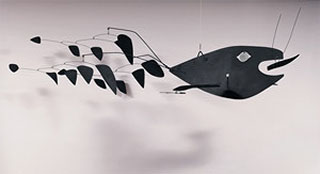

In the fall of 1931, a significant turning point in Calder's artistic career occurred when he created his first truly kinetic sculpture and gave form to an entirely new type of art. The first of these objects moved by systems of cranks and motors, and were dubbed "mobiles" by Marcel Duchamp—in French mobile refers to both "motion" and "motive." Calder soon abandoned the mechanical aspects of these works when he realized he could fashion mobiles that would undulate on their own with the air's currents. Jean Arp, in order to differentiate Calder's non-kinetic works from his kinetic works, named Calder's stationary objects "stabiles."

In his later years Calder concentrated his efforts primarily on large-scale commissioned works.

Some of these major monumental sculpture commissions include Man, for the Expo in Montreal (1967); El Sol Rojo (right), the largest of Calder's works, at sixty-seven feet high, installed outside the Aztec Stadium for the Olympic Games in Mexico City; and Flamingo, a stabile for the General Services Administration in Chicago (1973).

In his later years Calder concentrated his efforts primarily on large-scale commissioned works.

Some of these major monumental sculpture commissions include Man, for the Expo in Montreal (1967); El Sol Rojo (right), the largest of Calder's works, at sixty-seven feet high, installed outside the Aztec Stadium for the Olympic Games in Mexico City; and Flamingo, a stabile for the General Services Administration in Chicago (1973).

retrieved from Calder.org

August 6, 2009

More Alexander Calder work at the Calder Foundation web site.

Wikipedia on Calder