buzz's hot spot

|

|

|

Dr. Groves' analysis purports to be carried out to a precision of a ten-thousandth of a degree of arc. This implies he is able to locate the "hot spot" on Aldrin's heel -- not in the photo, but on the heel itself -- with a precision of 0.002 inch (0.05 mm), or less than the diameter of a human hair. That's astounding! The enlargement above shows the hot spot itself is much larger than the purported degree of accuracy. Further, the top of the hot spot is visibly displaced to the left compared to the bottom. And the print from which this scan was taken is likely "pushed" in development, possibly causing the hot spot to bleed into the surrounding emulsion.

Dr. Groves' arbitrary assumptions (well hidden in the book) coupled with his absurd purports of precision are clearly aimed at impressing a naive audience with apparent rigor while masquerading just how far off his computations can actually be.

WHY IT CAN'T BE A

STUDIO LIGHT

Percy claims that the extreme darkness of the shady side of the LM would have made any useful photography impossible. We have already shown that Percy's claim is naive. We shall next examine his claim that this photograph benefits from "fill" light provided by the lighting instrument he says created the hot spot on Aldrin's boot.

Lighting for photography (still and motion picture) often employs a "key" light which provides the main illumination for the scene and is positioned where it can cast shadows that establish the depth and texture of objects in the scene. The "fill" light is a weaker light used to soften the shadows and lessen the contrast between light and shadow. This allows the film to record lighted and shaded objects with a single exposure setting. The fill light is positioned to light the subject at the opposite angle from the key light.

Dr. Groves' claim to have precisely located the light source implies that the light is quite small. You can't precisely locate something that's large because it doesn't have a precise location. But here's the problem: small light sources cast shadows. If you want to light something without that light casting a shadow, you need a very large light source. This is why professional photographers use large reflectors and diffusers on their lights. Especially their fill lights.

A small light located slightly to one side of the photographer will cast very characteristic shadows, much like those in amateur photographs where the flash is just a short distance from the lens. The LM is festooned with details that would cast just such tell-tale shadows under the lighting. We see absolutely no shadows from the porch rail, or from the panel just to the left of the forward hatch. These are both in prime locations for the postulated light source to cast shadows onto the hatch itself.

If we wish to continue believing that an artificial fill light must have been used, we are forced to conclude that the light was very large, such as a huge reflector or diffuser. This flatly contradicts Dr. Groves' analysis which demands that the hypothetical light be very small in order that its location can be precisely computed. The soft, non-directional nature of the apparent fill light supports the hypothesis that it was a large light source. But is it really non-directional?

|

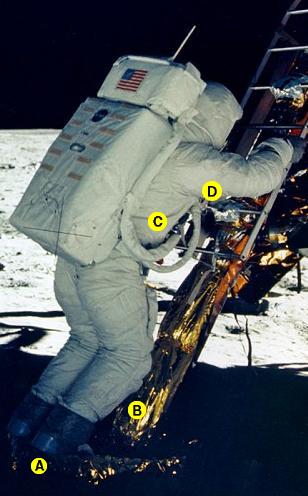

Note A. This is the "hot spot" Percy says is being caused by the fill light. This indicates that Percy's postulated lighting design applies to this photograph too.

Note B. Two characteristics of this portion of the photo interest us. The first is the relative dimness of the astronaut's legs compared to the rest of his suit which is more brilliantly lit. This indicates that those portions of the suit are not receiving as much light. This pattern of light is consistent with indirect lighting from the portions of the lunar surface which are directly lit. There would be just such a patch in front of the photographer, to the pictured astronaut's right.

The second feature is the apparent direction of the light. The inside of the astronaut's leg is shaded while the front part of the shin is lighted. Dr. Groves claims the fill light is only a dozen or so inches from the photographer. This pattern of light could only be produced from a light source that is generally much farther to the photographer's (and astronaut's) right.

Note C. The hoses which connect the astronaut's backpack to his space suit are casting soft shadows on the suit. Soft shadows can only be produced by large area light sources, not the small light Dr. Groves says is causing the hot spot on the boot. And the shadows are above the hoses, indicating that the light source casting them is below them. Indeed the hoses are only a few inches away from the suit, but the shadows are significantly displaced upward. This indicates that the lighting angle is very low indeed.

Note D. The astronaut's arm is shaded on the top and lit on the bottom. This is conclusive evidence that the source of fill light in this scene is coming from below the astronaut, not from the general direction of the photographer.

Big deal. All you've

shown is that the light source is a large area light source, and that

it's below the astronaut. This doesn't show Percy's hypothesis is

wrong.

Big deal. All you've

shown is that the light source is a large area light source, and that

it's below the astronaut. This doesn't show Percy's hypothesis is

wrong.

But it does. Since Percy can provide no direct evidence for his hypothetical light, a plausible alternate explanation refutes his hypothesis. Percy argues that it must be an artificial fill light because it can't possibly be anything else. Thus the reader is forced to accept a highly implausible hypothesis merely because he thinks it's the only possible one.

We have shown that a light which would produce the hot spot would also produce hard-edged shadows which simply aren't there. We have also shown that the fill light in this image is produced by a different kind of light than Percy postulates, and located in a different place than Dr. Groves suggests.

In fact we find that the brightly lit lunar surface is the best candidate for the fill light we see in the scene.

The appearance of the ladder in the photographs gives us a good indication where the photographer was standing relative to the lunar module. The LM's shadow would fall diagonally across the surface in front of the photographer from far right to near left. If the photographer stepped to his left enough, he would be in shadow. This means the lunar surface to the photographer's right should be brightly lit. This fully explains the indirect lighting as seen on the astronaut's suit: a large area light source coming from below the astronaut and to the photographer's right.

That still doesn't

explain the hot spot.

That still doesn't

explain the hot spot.

No. That's because the hot spot and the indirect lighting are produced by two largely unrelated effects.

SHINE YOUR SHOES,

COL. ALDRIN?

The real mystery is why silicone rubber shoes should produce a hot spot of any kind. Examples of these shoes can be seen in many museums and they are uniformly matte. David Percy, who claims to have examined astronaut boots, offers no explanation.

To understand why they shine in these photos the reader must know how Apollo equipment was used. The astronaut trained with space suit which was allowed to become worn with use. Then for the flight he was issued a brand-new space suit complete with new overshoes. He wore this suit only briefly to check it out and ensure a good fit. Then it was packed aboard the lunar module not to be taken out again until after landing.

The boots glisten when new. This is because of the mold process used to make them. The photos below

|

When Aldrin stepped down the ladder he was wearing a brand new pair of shoes that had probably never been worn.

The lubricant will wear off with use. Such use will also scuff and dull the finish, producing the matte finish we observe in photographs and museums.

AT LONG LAST, THE HOT

SPOT

NASA was particularly interested in seeing pictures of an astronaut trying to get out of the LM. The forward hatch had been made as small as possible and NASA needed to know if it was large enough, or even if it could be made smaller. Therefore Neil Armstrong's job was to photograph Aldrin as he climbed out of the LM, offer him directions, and describe his progress to Mission Control.

The sequence begins with AS11-40-5862 which shows Aldrin just emerging. The next photo is taken from a different angle, more to the side, and shows the tips of Aldrin's toes on the porch and his PLSS fully egressed. At this point Armstrong apparently got bored and took two photos, one of the area underneath the LM and another of the LM's left footpad.

These photos are significant because both show lens flares. A lens flare can only occur if the lens itself is in direct sunlight. These photos establish conclusively that Armstrong was standing in direct sunlight at this point.

|

Armstrong's position in sun or shade is important because a sunlit space suit is a very bright thing. The space suits are brilliant white and are made to reflect as much light as possible for thermal control. In later missions the space suits got quite dirty, but Armstrong and Aldrin weren't allowed to do the things that others did to get dirty.

Dr. Groves maintains that the light source is just to the right of the photographer. Very close to the photographer, in fact. But when his cavalier assumptions are taken into account, we realize that he can't really be that sure. The light source need not be near the photographer. We contend that the light source is the photographer. That is, the hot spot is a reflection of Armstrong's brilliantly illuminated space suit.

You can't honestly

expect us to believe that such a bright hot spot is caused only by a

white space suit lit by the sun.

You can't honestly

expect us to believe that such a bright hot spot is caused only by a

white space suit lit by the sun.

All things being equal that would be a hard hypothesis to swallow. But David Percy himself provides the answer. While we contend that the shady side of the LM wasn't in pitch darkness, nor do we contend that it was especially brightly lit. Armstrong would definitely want to make adjustments to the exposure in order to get a good photo in relative shadow. But of course he could only adjust it so far. He would want to open the aperture all the way while leaving the shutter speed relatively fast to avoid motion blur.

|

But this may not have been enough by itself. The photo lab can "push" the exposure when creating prints, making a print that's lighter than the original transparency and possibly revealing more contrast. Digital scans taken from prints of these photos are uniformly brighter than scans taken from the master transparencies for the same photos. Since it's possible to "push" individual prints, but not advisable to do it for entire transparency rolls, we hypothesize that the prints of this photo sequence are customarily "pushed" in the photo lab to make them more suitable for display. And since we have reason to believe that despite Armstrong's best attempts at overexposure, the areas of interest in the photo were still too dark, there is a plausible motive for the photo lab to "push" the prints.

This means that a highlight which was comparatively dim in the original transparency may appear considerably brighter in a "pushed" print.

There are very plausible alternatives to Percy's insistence that only studio lighting could produce this photo.