image quality

|

NASA: AS17-134-20376 |

NASA: AS17-138-21028 |

NASA: AS17-140-21351 |

Many photographs contain lens flares because they are up-sun segments of panoramas used to document the surroundings of important events in the checklist. These photos are important to the scientists studying the returned samples, but are not usually interesting to the general public. The scientists use them as documentation and ignore any aesthetic flaws they may see.

Below are two photographs in which light has leaked into the magazine. This sometimes happens to the last picture on the roll when the astronaut removes the film magazine from the camera, especially if the photographer has not wound the film fully into the magazine. These images are said to be "sunstruck". In the first image a streak of white completely obliterates the left side. In the second image the upper left corner has been given an orange tint, but the details are still visible.

NASA: AS16-112-18273 |

NASA: AS16-113-18380 |

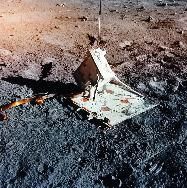

The rest of the images below are flawed in some way. Some have lens flares or are poorly focused or strangely framed. While they are still valuable, they are not perfect. The point is not to argue that the astronauts were poor photographers, but that the photo record indeed shows that the photographs were taken in an uncontrolled environment with a high proportion of imperfection.

NASA: AS12-46-6715 |

NASA: AS15-82-11201 |

NASA: AS12-46-6738 |

NASA: AS16-105-17220 |

The Hasselblad cameras

didn't have viewfinders, automatic exposure, or automatic focus. How

were the astronauts able to get any good photographs at

all?

The Hasselblad cameras

didn't have viewfinders, automatic exposure, or automatic focus. How

were the astronauts able to get any good photographs at

all?

Believe it or not, people were able to take good photographs before automatic exposure computers and automatic focus devices were invented. It required a bit of training and practice. Film manufacturers commonly provide exposure guides giving the average correct camera settings for common lighting conditions.

The exposures were worked out ahead of time based on experimentation. The ASA/ISO rating of the film was known, and NASA photographers precomputed the necessary exposures. These figures were refined over the course of the program. In many cases the camera settings for planned photos were given in the astronauts' cuff checklists. In other cases the astronauts followed some basic rules.

Automatic exposure controls were available on several consumer camera models during the late 1960s. Apollo 11 Command Module Pilot Michael Collins suggested that Hasselblad look into the possibility of incorporating this technology into the camera after his experience on Apollo 11. Apparently the professional photographers who used the Hasselblad model upon which the lunar surface cameras were based did not want automatic exposure controls on their cameras and so it was not a standard feature.

Shutter speeds were typically 1/125 or 1/250 second. F-stop settings varied from f/5.6 for up-sun photos to f/8 and f/11 for cross-sun and down-sun photos.

The lack of viewfinder was occasionally a problem. Early missions

used a wide-angle lens. It was sufficient to point the camera in the

general direction of the subject and you would be likely to frame it

well enough. On later missions a 500mm telephoto lens was also taken,

and the cameras were modified with sighting rings to help aim them.

Normally the camera would be mounted on the space suit chest bracket,

but for telephoto use the astronaut would have to remove it and hold

it at eye level in order to sight down the rings.

FOCUSING IN THE

ZONE

Manual focus is not as problematic as many suppose. Lens manufacturers mark the expected distance to the subject on the focus ring, and it's simply a matter of measuring or estimating the distance from the lens to the subject and setting the ring for that value. To aid the astronauts in measuring the distance to subject, length of commonly used tools was marked on the lens. Several Apollo photographs show the tongs and scoops used as distance references. Focus need not be exact either.

The Apollo astronauts were trained in "zone focusing", a technique used by photojournalists and sports photographers who often don't have the time to focus visually or by measurement. At a high f-stop, a camera's depth of field increases. This means that when the lens is set to focus at a certain distance, objects somewhat nearer and farther from this ideal distance are also sharply focused. The narrower the aperture (i.e., the higher the f-stop), the greater the depth of field. And the sloppier the photographer can be be about his focus setting. The Zeiss Biogon lens used by the astronauts had an indicator that specified the near and far boundaries of the depth of field for each combination of focus and f-stop.

Zone focusing is a technique whereby the f-stop is kept high,

resulting in lenient depths of field. The focus range is then divided

into "zones" corresponding approximately to near, medium, and far.

These zones of clear focus overlap slightly and correspond to preset

positions of the focus ring. The Zeiss Biogon lens provided to the

astronauts had "detents" or click-stops that corresponded to these

three zones. The astronaut had simply to push the tab on the focus

ring to one of three easy-to-find stops to select the focus zone

depending on the rough distance to the subject.

But that's changing horses. The original argument was that they

were all (or in large part) of suspiciously high quality. Anyone who

examines the full extent of the record for himself finds that not to

be the case. The authors have made an assertion and supported it with

selective evidence. Now confronted with the true character of that

evidence, the authors change the direction of their argument without

closure on the original issue..

The authors have been caught with their homework undone, and

raising different suspicions does not excuse that. Either they have

not extensively examined the record, as they claimed, or they have

deliberately mischaracterized the record to their readers. Either

way, we cannot trust these authors.

But every photograph in

the Apollo record still contains numerous anomalies. [Bennett and

Percy]

But every photograph in

the Apollo record still contains numerous anomalies. [Bennett and

Percy]