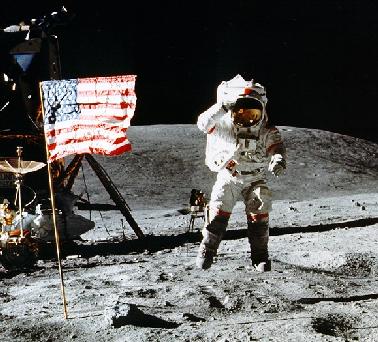

jump salute

|

|

If the flag were waving in the breeze we'd expect it to billow differently in photographs taken seconds or minutes apart. Instead the folds don't change between photographs. The flag is obviously stationary, but wrinkled.

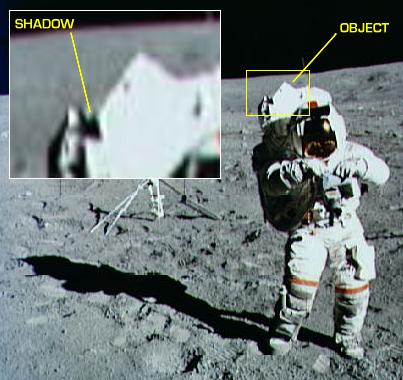

The object behind the

astronaut is in shadow, yet we see it clearly lit.

The object behind the

astronaut is in shadow, yet we see it clearly lit.

The object behind John Young's right leg is the Schmidt camera (essentially an all-reflector telescope using photographic film instead of an eyepiece) used for ultraviolet astronomy photographs. The lunar surface is the ideal place from which to make ultraviolet observations because the lack of atmosphere affords an unfiltered view of the universe. The slow lunar rotation allows long exposures without requiring tracking equipment.

A backup camera is on display at the Johnson Space Flight Center.

|

|

Fig. 3 was taken on the lunar surface and shows the UV camera's legs and part of its body. You can indeed see that it is sited in the shadow of the lunar module to shield it from the glare of the sun. But it was only a foot or two inside the shadow; the brightly sunlit portions of the lunar surface are not too far away.

Fig. 4 answers the question. It shows astronaut John Young training with the UV camera prior to departure. If you examine the aperture barrel where it joins the camera body and the diagonal structural stiffener that runs from the inclinometer to the base, you can see that the camera body is very reflective. In fact, it's only slightly less reflective than the lunar module's insulation.

The camera body reflects fuzzy and distorted images of the brightly lit surrounding lunar surface, even though the lunar module is casting a shadow over the camera.

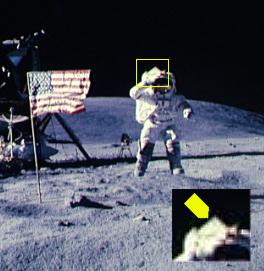

The triangular object

above John Young's head is the dangerously unfastened cloth flap from

his PLSS. As shown in the photo below, taken from the same instant of

the live television coverage, the flap is not visible. This proves

the still photo and the live television coverage did not photograph

the same event; one must have been prepared at a different

time. [Mary Bennett and David Percy]

The triangular object

above John Young's head is the dangerously unfastened cloth flap from

his PLSS. As shown in the photo below, taken from the same instant of

the live television coverage, the flap is not visible. This proves

the still photo and the live television coverage did not photograph

the same event; one must have been prepared at a different

time. [Mary Bennett and David Percy]

|

Here and elsewhere the authors base their arguments on suppositions such as blind, rigid, and almost religious adherence to pre-established procedure. They convey their impression of space travel as an almost magical undertaking that falls apart when the least detail is disturbed.

In fact, the astronauts were frequently qualified engineers and in many cases developed the procedures they themselves would follow. They are not, as Bennett and Percy might characterize them, simply acting out a script written for them by someone else. They are following their own notes worked out during practice runs.

Apollo 16 was given an abbreviated suit donning procedure in order to make up for their late landing. Some checks were likely omitted or done hastily. The astronauts themselves would know which steps were strictly crucial and related to life-threatening systems, and which were redundant or relatively unimportant.

With the nits out of the way we can concentrate on the meat of the issue. The flap the authors identify in the Hasselblad still photo and whose absence is noted in the video record is not the PLSS flap they claim it is.

|

|

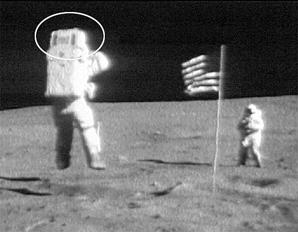

Percy and Bennett expect to see the rear PLSS flap and so they look only at the rear of the OPS in the video coverage. If we replay the video and instead look at the front of the OPS, where the object is really attached, we can distinctly see an object flapping back and forth as Young jumps and salutes.

|

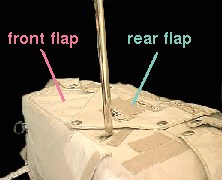

Fig. 8 shows the top of the OPS with the various flaps and panels which comprise the top surface. The object in the photos above can be clearly identified as a triangular flap attached at the front edge. Here is an enlargement with the panels labeled in color. Since the rear panel overlaps the top panel it is not difficult to see how the front panel could be retained in a vertical position by the rear flap if the rear flap were unfastened.

It's disappointing to make this discovery. Bennett and Percy argue from the basis of a claim to have extensively if not exhaustively examined the Apollo record. If this were true they could have hardly missed something like this, which required Clavius researchers only about half an hour to locate. Clearly the authors are either lying about the depth of their research, or else they are deliberately withholding information that they know contradicts their conclusion.

Since cloth is too

flimsy to remain in the upright position, it must have been fastened

there by a whistle-blower. [Mary Bennett and David Percy]

Since cloth is too

flimsy to remain in the upright position, it must have been fastened

there by a whistle-blower. [Mary Bennett and David Percy]

A good example of piling baseless conjecture upon baseless conjecture. When the rear flap was fastened its point would press against the base of the front flap, holding it upright. Far from being flimsy, the fabric was composed of several layers and quite stiff enough to avoid folding over in lunar gravity.

There is no need for a hypothetical whistle-blower in this case, since the behavior of the flap is fully explained by the circumstances. Further, such a visible "whistle-blow" would have been easily spotted by other workers and inspectors on the postulated film set.

Two cameras recording

the same scene must record the same details. [David Percy]

Two cameras recording

the same scene must record the same details. [David Percy]

Not when the cameras record the action from completely different angles, and one is a still camera and the other a motion picture camera.