Note: An early draft

of this document makes it clear this was written by Grandma Josephine for Dad

(i.e. like the Uncle Doug history).

It may have been when he was a teen, or even older, and perhaps done in an

attempt to encourage him to finish it himself? :-)

For the benefit of my posterity I shall attempt to write the story of my life. Starting at the beginning, with mother's description of me at birth.

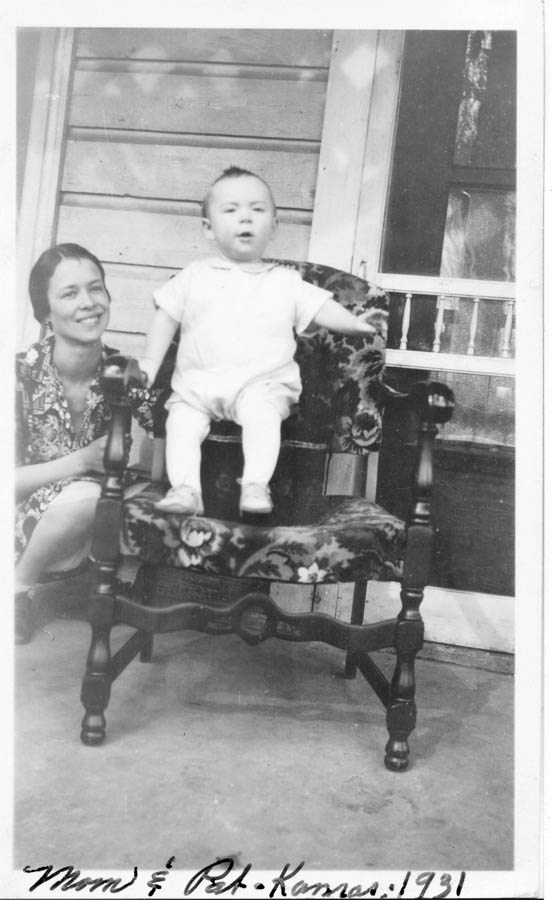

I was born February 9, 1930 in the L.D.S Hospital at Salt Lake City, Utah to Josephine Mitchell and Parley Rhead Neeley. My parents then resided at Kamas, Utah where Dad was then employed by the United States Bureau of Reclamation building the Provo-Weber Diversion Canal.

Dr. Warren Sheppard brought me into the world. I weighed at birth 8 I/4 pounds and was 24 inches long, with long black hair long enough to curl up at the neck) and was as red as a beet. Due to the difficulty in getting here via a small mother, my head was misshapen, sort of pointed, but to mother I was beautiful.

Aunt Veda, Dad's sister, then a nurse in the L.D.S. Hospital, had a new bright pink blanket saved for my arrival. Needless to say, mother was worried about the out-cropping of Dad's Indian blood when she first saw me. My head soon shaped up, my skin lightened, and my eyes turned brown and stayed that way -- the only member in our immediate family with brown eyes.

I was a husky baby and grew rapidly. My only sicknesses were caused by enlarged tonsils, which caused rheumatic fever when I was three. This was a mild case and other than resting three hours a day, going to bed early, and eating a well-balanced diet, I was allowed to play out as usual. We then lived in Arizona and most of my waking hours were spent out-of-doors. In May of 1933 mother and I came to Utah a month before Daddy to have my tonsils taken out. Uncle Jake, Dr. J.W. Bergstrom of Cedar City, did the tonsillectomy. I complained at the first whiff of ether and Uncle Jake said:

"Why, that’s just perfume. take a deep breath.”

"Well, I don't like your ‘perfment’. Take it away."

I can remember some of the things I did when I was two. I played with the Mutch girls, Nadine and Patricia. Once when they played with me while their mother was going to town, she kissed them good-by and started up the street. I felt disappointed, hollering: "You didn't kiss me Mush!” ... she came back giving me a kiss and hug. I remember too, of walking through an empty lot to get milk from a little market next to us at Wellton. It was a big responsibility for a two-year-old, especially since milk then came only in glass bottles.

Since we moved often, I was not allowed to have a pet. My comfort was a soft down pillow and I couldn't go to sleep without it. I lost it once and my parents made believe they didn't know what I was asking for when I was put to bed. Finally, after many trials, I said it plain enough for them to understand "Pill- aw”. Dad searched outside where I'd played and found it, I was soon asleep. Two years later I left it in a motel at Idaho Falls and had to have it sent by mail.

When I was two and a half we lived in Green River, Wyoming for a few months. I was crazy about trains; I sat at the window by the hour watching the trains as they were switched around, made up, and sent on their way again. The yards were near our home and I loved the excitement of the puffing engines and shrill whistle. A year later when mother and I came to Utah ahead of Daddy my dreams came true when we rode the train. Mother tells of my delight at finding a lavatory with toilet and a bright metal "wash hands" right on the train. Needless to say, my hands needed washing often on that trip.

The following winter we lived at Parker, Arizona where father was doing investigation on the Los Angles aqueduct. Our friends, the Gilby Smiths, took a walk with us to the Colorado River. We took our lunch and Colleen stuffed a daisy bud up her nostril. Her mother was in a frenzy trying to get it out, Colleen was crying. Mother took over saying, "Colleen blow your nose, and blow it hard!” As Colleen blew Mother gave her a firm slap on the back and the daisy bud popped out like the cork of a pop gun.

On the way home, a jerry car on the railroad track carrying a half dozen Mexican men offered us a ride. I wanted desperately to accept their offer, but Mom thanked them and said "no!" I teased but to no avail. The Callan's shared our house or apartment. One large room partitioned with government flagging (un-bleached factory) served as living quarters for both families. We had a little pot-bellied heating stove which burned iron wood. Often mother had a pot of soup or beans cooking on the top of it. For a cook stove we had only a two-burner electric plate. For Christmas Santa brought me, among other things, a wind-up train and tracks to run it on. I ran it off of the track, it went under the refrigerator, and as I grabbed for it cut my finger on the spinning cog wheels -- the scar from which I carry to this day.

Three things I remember from our stay in Blythe, California. While we were house hunting a man at a real estate business offered to show us a home, as he stood up, from his desk, I noticed he had no legs, just feet and ankles. I wanted to ask about him, but mother squeezed my hand each time I attempted to ask. We rented a house from a doctor who sent his colored maid to help us get settled. Mother took me aside and explained about Negros, telling me not to ask questions. I watched her work around and finally asked: "Why is the inside of your hands so much cleaner than the outside?" She only laughed.

I made friends with a retired judge who came by our place each day at Blythe on his way to his vegetable garden. He spoke kindly to me so one day I asked him if I might go with him. He said yes if I'd get my mother’s consent. Each day after that I watched for him and we'd go hand in hand to see what his garden was doing. We sat and ate a carrot or turnip while he rested, and he included me in his plans saying, "One of these days we'll have to dig those turnips out, they're getting woody." I liked turnips, but the day came when the judge said, “Well, the turnips have gone, we'll have to pull them up." I told mother that the “turmits” had all turned to wood so we couldn't eat them.

Our neighbors, whom Dad and Mom called the “Okies" kept huge channel cat fish in a tub of muddy water just outside their door. At suppertime the Mrs. Would pull one out, chop off its head, and cook it for supper. I didn't like fish after that for a long time.

One of my earliest memories was the trip to Catalina Island with my parents when I was three. The ship was large and the excursion crowd jolly, excited and noisy until we got out in the ocean and the passengers began to get sea-sick. “Here Mon, hold my gun.” Mother asked, "Are you sea sick?" She said she needn’t have asked had she first looked at me. I was pale, with freckles standing out far enough to be brushed off. After I emptied my stomach Dad walked me around the deck while mother joined the line in front of the sick bay. After we disembarked and ate I was ready to try all the gimmicks awaiting the tourists, even the glass bottomed boat. Such a variety of fish; especially interesting were the seals that basked in the sunshine on the rocks.

The following summer we lived at Lyman, Wyoming in a little doll house owned by an old couple named Boss. Dad's work as an engineer for the U.S.B. of Reclamation took us from Wyoming in the summer to Arizona and California in the winter. Mother was not far wrong when she said that we have lived in all the little hamlets from the Canadian borders to Mexico, along the Colorado River and its tributaries -- staying only a few months in each place.

The Boss's grandson, John Lee, was my playmate at Lyman. He carried a good pocket knife and chided me because I didn't have one. He was two years older than me. Together we went to ask mother if I could carry one of Dad's knives. She said no. That I was too young, and that John Lee was also too young to carry such a big knife. She was proved right when five minutes later John Lee came crying into our house, holding a bloody hand. Yes, his pocket knife was sharp, sharp enough to cut off rabbit ears as he'd boasted, and fingers too!

Aunt Kathleen visited us in Lyman. I teased to go to the show with them and mother said that the show would not be interesting to me and that I'd go to sleep and be miserable when I awakened, spoiling the show for the rest of us.

“I won’t cry", I said, “If I get sleepy I’ll just go home without myself."

Fascinating to me was the big road grader (“crader”, I called it) that rumbled back and forth building a highway in front of our place. I longed to ride on it and maybe operate it. I was not allowed to go beyond the gate, and mother checked often. When the men stopped for lunch in the shade of the trees by the gate I asked them if they wouldn't let me ride with them.

“Sure, if you'll bring us a fresh piece of pie", one said.

My hopes soared; I fled to the house. Mother had no pie but had some freshly baked cookies. They settled for the substitute. I ate a hurried lunch to be ready when they began. They put me in a safe place and told me not to move, there I stayed for four solid hours, enjoying every minute of it. Dust covered and wet I was removed at quitting time. Mother looked at my wet pants disdainfully but said nothing.

I quickly explained: "I told the men to stop that I had to tinkle, but they just went on” and Mother understood that I'd tried.

The summer we spent at Lyman was a happy one. I was then three and a half years old. Mother had told me that we were going to get a baby by the time I was four. I was excited, now I would have someone to play with, and I had no doubt but that it would be a boy. To my parents delight, Dad was transferred to Ogden that winter and due to the arduous task of finding a suitable apartment our baby was born a month too soon -- December 11, 1933. Mother's sister Belle and husband Hal stayed with us while Mom was in the hospital.

The day Mom brought my baby sister home I was all scrubbed up ready to play with her. One look at the tiny squirming infant and I said: "Is that all the big she is?" and went out to find a more suitable playmate. I remember the friends I made which also lived in the Flowers Apartment. One, Jimmy McPhillemy, a year or so older than I, introduced me to a new kind of fun, that of putting tin cans and cardboard boxes on the street car tracks and listening for the Conductor’s swear words as he got out of the car to clear the tracks. Mother soon put an end to that.

Come spring we moved to a little house on Van Buren (2966 “Ban Boorian” to me). We had a large lot with a field behind our fence where the neighborhood kids played. One day mother placed my baby sister Barbara, then about six months old, on a blanket on the back lawn and asked me to watch her. We played together for a time then I found other interests, forgetting the baby. When I remembered to check, there was a large snake making its way toward the baby. It was already on the blanket. I ran to the house telling mother to come quickly there was a big thing, like a chain, and I made a motion with my arms. Mother reached Barbara just as the snake touched her dress. Snatching the baby up she screamed for the neighbor, who was in his yard taking the water turn. He came with his shovel said it was only a blow snake and quite harmless, but he killed it, cutting it into three pieces. I gathered up all the neighbor kids I could find to come and see the "remains" where Mr. Crittenden had flung them in the field beyond.

Rudy and Jim Callao lived near us on Thirtieth Street. They didn't have any children and I liked to visit there. Besides Rudy made doughnuts real often. One day I asked for one and she taught me a lesson I never forgot.

She said “Pat, I like you and would give you nearly anything, but it is not polite to ask. When I have doughnuts, I’ll offer them to you, but please don't ask.”

I remembered and never asked again, but I hadn't promised not to hint.

"Rudy those doughnuts surely smell good”, or "Rudy you surely make good doughnuts".

Rudy declared that I could smell her cooking doughnuts a block away.

About this time, I decided that I didn't like red meat, probably because I'd watched Grandpa Neeley and Dad cut a venison up. “I don't like any meat but just ham and bacon. It doesn't come from any animal, it just comes from the store,” I said.

We spent the last two years of the four we lived in Ogden on Ogden Avenue. There were lots of kids there. My closest friends were, Andy Wheeler, Sammy Jackson, George Tracy, and the Rushforth sisters -- Geraldine and Gwenny. The summer I was five Mrs. Wheeler had a kindergarten in her home. She was an excellent teacher and I was eager to learn and so when September came Mrs. Wheeler recommended that I be allowed to enter public school, even though I was a year too young. Since I was large for my age and even more mature than some of the six-year-olds, the school accepted me. There were already too many children for the first-grade room, we overflowed into the hall, but with an assistant teacher -- a pretty, young Miss Williams -- everything went well. The regular teacher, who was I would guess older than the sixty-five . . . retirement age, was slightly built, with gray hair and a thin, quiet voice was Mrs. Reese. I liked her and listened intently to catch every word.

Mother wanted me to take the responsibility of getting to school on time, so she showed me that when both hands of the clock were on nine it was time I was on my way. I'd get ready early and then play with Barbara, sometimes barely making it to school on time after running three blocks. One morning Mother didn't remind me but let me play around until 9:30.

When I noticed the time I got excited saying, "I won't go to school this morning, all the kids will laugh at me."

Mom said, "Oh yes you will, if I have to take you.”

That settled it. I didn't want the kids to see mother bringing me to school. I got a reprimand from the teacher; that was the last time I was tardy.

An incentive for going early to school was to watch Mrs. Brown comb her hair. She'd come with it in small, tight braids, which made it real kinky, giving it body enough to hold a bejeweled comb behind the tiny knot on the top of her head. I thought it looked good, anything she wore or did had my approval, I liked her so well. She was a fine teacher.

Dr. Rasmussen, our neighbor and a veterinarian, brought me a spotted black and white terrier pup. When I slept on the screen porch she slept on the foot of my bed. I was careful not to let her get on the new quilt that mother had pieced purposely for my bed. Budgy barked a lot and once at least that barking saved our trailer. It was tethered to a tree in the back yard and before the thieves could loosen the chain, Budgie had awakened Dad and as soon as the lights came on the thieves ran.

Every Sunday afternoon when we'd take a ride. I'd tease to go to the train yards. After watching a while we'd go home by way of Farr's Ice Cream Parlor, no deviation was allowed. Double deck ice-cream cones then sold for 10 cents and the 5 cent ones were generous. This was a prelude to Sacrament Meeting which we never missed.

Dad was a counsellor in the Bishopric of Ninth Ward. The chapel being just two blocks away, we walked to our meetings. It seemed to me that we spent a lot of time at the church. Tuesday, we went to Relief Society, and after that to Primary, and in the evening to Mutual Improvement Association. I didn't always go to MIA, just when there was a special program or a ward party. One evening I ran home from the church to go to the bathroom. Of course, the door was locked and in fiddling around trying the back door and windows I wet my pants. I was six or seven and ashamed, so I didn't go back to the party. When my parents couldn't find me, they guessed I’d gone home and there found me sitting on the front porch with wet pants. “Why didn't you go out behind the tree in the back yard,” Mom asked.

"You told me never to go outside but to come to the house; I tried.”

This very thing disgusted Grandpa Mitchell when we visited him at Parowan. With cousins Jim Lindsley, Billy Gardner and Clark Mitchell, we be at the corral with Grandpa and keep running to the house to 'tinkle' in the toilet. There was a 'two-holer’ in the orchard, but we preferred the flush kind. Grandpa's disgust was perhaps because they had only a septic tank and continual flushing hastened the filling of the tank and made digging another necessary.

Our brother, David Mitchell, was born July 20, 1937, in the Dee Memorial Hospital. He was a big, husky baby. Mother contracted pneumonia right after his birth and while Dad had then received his transfer to Montana was unable to go until mother got better -- which was six months later. Dad left for Glendive December 9, 1937 where he was to build the Buffalo Rapids Project. We followed by train December 23rd, after Dad had found living quarters for us.

All Ninth Ward turned out to see us off. Gifts of food, games and candy ladened us down as we boarded the train. David then weighed 20 pounds and was all mother could handle bundled in blankets to shield him from the winter wind. We had a state-room reserved and to our delight a ring of the bell brought a porter who kept-his black face in the door until we’d given him a quarter. Babe and I rang the bell often just to see if he would appear; he waited for the tip even though he did nothing for us. Mom stopped us by saying that we couldn't eat on the train if we gave the porter all our quarters.

I tried to take care of David while mother and Barbara went to the dining car. I tried my best to hold on to him. He wriggled and rolled and somehow ended up on the floor. A kind school teacher came to my rescue, letting me go to eat with Mom and Babe. Dad met us at Billings, he took over while mother rested, she’d used up her last ounce of strength.

I was seven when we went to Glendive, to be eight the following February. Although Barbara was four years younger we enjoyed playing and doing things together. We lived in an apartment in town, renting from a banker named Banker. Advertised along the street was the first of the "sex" movies with Jean Harlow starring. We teased to go to ‘Souls at Sea' and thought our parents stingy when they refused to let us. We left the apartment to live in a little cottage on the east side of the railroad tracks. We hadn't moved soon enough for we learned that the couple upstairs had bed-bugs and they were beginning to come down the plumbing pipes into our bathtub. Mother and Dad were horrified, and I was so impressed with the situation that I wrote a theme and some poetry on this exciting subject. Mother learned about it from my teacher, who told her that I chose peculiar subjects for my original writing. Well! It was truly news; we’d never encountered the blasted things before. Although it was 10 below zero the day we moved we hung everything we had, in the line of clothes, bed clothes, linens, etc. on the clothesline to make sure we didn't take dirty things with us.

The missionaries found us at our new home and the Ferrell Andersons, also LDS, lived only two blocks away. With this nucleus we started a Sunday School, and finally, a Sacrament Meeting and Primary. The Andersons had two boys both older than me, but our common bond of religion made us close friends.

Mrs. Sohme, a Catholic, owned our home, and also a little market on the corner next to us. She sat on our porch each Sunday night and listened to our Sacrament services, even after the weather was cool. Of course, we had invited her to come in, but she always said that the Father (“Fodder”) wouldn't want her to. We watched the trucks drive in and out of the driveway to be loaded or unloaded at the market. Mother didn't allow us to take nickels or pennies to the store for "trash". She called penny candies "stuff" and "trash."

One day I watched the proprietor of the market paste a big sign on the side of his building. I could read, and it said: "Come in and Sample our fine Butternut Coffee. (Introductory offer).” Now I knew about the Word of Wisdom -- we never had coffee in our house -- but I suddenly had a ‘yen’ to try it. Looking for someone to share the blame, if indeed there were any, I found Barbara and we went together to try the free coffee. We sat at a small table and a cup of coffee and a small cookie were brought to us - no sugar or cream. I felt guilty and hoped that Mother and none of the Andersons would catch us there. One thing that cup of coffee taught me was that coffee is not as good as it smells. Mormon tea is a whole lot better, and it's not bad for us. Just a cup of hot water with cream and sugar.

School in Glendive was different. The third-grade room was crowded. The teacher, Miss Fullford, acted dismayed that she had to have one more pupil, saying,

“I don't know where I'll put you. You can sit in Tony's seat today but when he comes back you'll have to move."

I ended up sitting in the absentee's desks as the various kids were out because of sickness.

Everybody looked at me. My freckles had never been so brown and so numerous. Mother could call them sun-kisses, but those Montana kids didn't seem to know about sun-kisses. I didn't meet their glances. I looked at the floor. When the teacher came along our isle I wondered how a woman could possibly have such big feet. Learned later that her shoes were size 14 EE. ‘Fullford’, as we called her, was sensitive about her feet and resented the taunts of the ‘smarty boys’! She was essentially a thorough teacher if a little on the brusque side.

I made some good friends at school; there was Jug-head, and ‘The Italian boys’. We climbed 'Hungry Joe', the highest hill to the east of us, and in the winter, we skated on the ice and tobogganed. At home my hobby was putting together model airplanes. One was so fascinating that I hurried home at lunch time to work on it. It was just my luck to spill the cement on my school trousers Mom had made for me out of Dad's brown wool pants. A quick swipe with the washcloth convinced me that the glue was there forever so I hurried off to school before Mom could see the mess.

The missionaries were often guests at our home. We had a bedroom, of sorts, in the basement, where the boys would pile three in a bed if necessary. One night a pair said they were going to meet a new missionary at the train depot at midnight and could they bring him back to sleep with them? In the morning as the smell of breakfast bacon alerted the boys that it was time to eat, up came five big strapping boys. I thought mother would faint as they were introduced.

Later that day a funnel shaped cloud brought heavy winds and an electrical storm. As we sat visiting, the missionaries on one side of the living room, and our family on the other side, a ball of fire passed between us from the open window in the kitchen, and thru the open window in the living room. A hissing accompanied it, and instantly it started a fire on the house across the street. We felt that the kind hand of providence had preserved us.

More than once Mother took us children to visit in Utah by train and Daddy would come later to bring us home. We kids would always speak to sleep in the upper birth while mother and the baby would sleep in the lower. Climbing the ladder to our births was fun and gave us an opportunity to work off some of the pent-up energy we’d saved during the day. I’ll bet half the passengers on our car would have liked to throttle us. Mother finally resorted to a belt strap to settle us down.

We always had such good times at Grandpa Mitchell's in Parowan. Grandpa would let us ride the horses and go with him in the wagon to the farm where we'd pick all the corn we wanted to eat. We’d ride to the canyon to find the horses or cows, eat at the sheep camp -- good sour dough bread and fried mutton. Gramps would give us doggy lambs, but when it was time to go home we'd have to leave the pet lambs. Once all the cousins were at grandpa's when he had to load some pigs in the wagon to take them to the ranch for the summer. Jim, Bill, Rosemary and I were old enough to give real help and we'd managed to get all the pigs, but one old boar loaded. Finally, we had him going up the double plank ramp with Grandpa carefully guiding him when Rosemary threw her hands in the air and yelled, scaring the boar. He reversed directions and somehow Grandpa landed astride his back and down they went. Grandpa was “proper blazing" after all the difficulty we’d had to get the pig loaded. He sent Rosemary to the house and wouldn't let her go with us.

The "big five" was a term applied to us five, boys,

cousins, who were within a year and a half of the same age.

Bill Gardner was the eldest, Jim Lindsley, next, then, Hal Mitchell, then

myself, and Clark Mitchell the youngest. We

were all good sized for our ages. and got along well together.

Such fun we bad roaming the hills, riding the horses or helping grandpa

with his chores. One hot June day we

hiked to the ‘P’ on the hill. It

didn't look far, nor too steep, but it was a challenge and once was enough.

--The End -- . . . this was as far as she got . . . and Dad never took over . . .