Source for these stories: 'William Cooke Mitchell Family History Collection', first compiled by Margaret Mitchell Blackhurst from 1970 to 1983 and updated and reformatted by The Mitchell Cousins from 2005-2012. This is a 246 MB file, than can be downloaded, from here.

Note: To save space, and typos, the three William Cooke Mitchell's will be often referred to as WCM I, II, III. If you want to know how I fit in here, see this personal note.

You can browse through the stories, or jump to a specific story by clicking on the hyperlinks below:

A Mariner and a Whale Hunter . . . a Methodist Preacher . . . and seeker of Truth

WCM I "was a mariner and whale hunter in the North Sea, off the Isle of Man" -- p. 5

He says of himself (original spelling retained):

"I was taught the Metodist reglion but when abot 17 years old I commenced

reading the Bible and New Testment and Prayed to understand & found out that

their was no Gospell Preached acording to what was Preached by our Savior & his

Apostles. When I inquired of our Teachers they told me that is [sic] was done

Away. I then settled down untill 1830 and from that time untill I saw Elder

Taylor & Joseph Fielding I never found any rest for my mind." -- p. 5

He wrote of his conversion as follows (again, original spelling retained):

"February 1840 Elders Taylor & Fielding came into the Chapple I blonged to. I took them home to my house and after investigating the Princibles they Advanced I became convinced that Joseph Smith was A Prophet of the living God for the Holy Gost fell on me and went through my sisteam [system] like A fire and A voice Saying these are my Servants. We obtained A Place for to Preach in and Elder Taylor gave A discourse from the 24th Chapter of Isiah. As soon as he was through I asked A Privlidge to speak. I got up and bore Testmony the man Joseph Smith was A Prophet and that the Brethren was the Servants of the living God. I then offered myself for Baptism & one of my Classes followed me and we was all Baptized in the Sea at Liverpool. I was soon turned out of my imploy and in the fall of 1840, I was sent to Manchester Conference." -- p. 6

“Parowan” does not mean bad water, or stinking water, or stagnant water, or salt water – definitions that have been given – but literally means wicked water" -- p. 172

"According to a story told to the late Indian authority William R. Palmer by Old Susy, an old Indian squaw, the daughter of Chief Owampa, the translation of the word Parowan means “mean or wicked water.” Pah means “water” and ruan, “evil or mean.” The name had its origin in a legend which says that at one time when the Indians were camped near Little Salt Lake the water rushed up and stole a man. He was carried far out and was never seen again. They say that the lake bottom had holes in it and that the water sometimes jumped highup. There may have been volcanic disturbances there, or a temporary geyser jet." -- p. 145

Bravery and kindness to an Indian boy . . . which ends in 'target practice' (as told of WCM II, who helped establish Las Vegas, Nevada)

[WCM II served a mission in Las Vegas, as one of a pioneer company who traveled there in 1855 to establish a fort, and] "to establish a halfway place between Salt Lake City and Lower California for the protection of travelers against the hostility of the Indians. The other object was to develop friendliness with the Indians, and to civilize and Christianize, if possible, the roaming tribes of savages." . . .

In the spring of 1856 after the crops were planted at Las Vegas, William II made a trip home to Parowan to burn tar and trade it for provisions with which to sustain himself during the coming year. As a means of establishing a more friendly relation with the Indians, it was decided that he should have an Indian boy accompany him on the journey. After traveling as far as Santa Clara [Washington County, Utah, near St. George], they encountered a tribe of Indians, which showed their hostility by saying that they would not allow the Indian boy (who was not of their tribe) to continue the trip, and even went so far as to threaten his life. They surrounded the wagon and demanded that the boy be delivered to them. But William II stood with rifle in hand and faced them, telling them in no uncertain language that if they made a further move he would fire. He then decided that it would be better to have the boy return home. He told the boy to start, for he knew if he could but detain the Indians until the boy was out of sight there would be no danger of their overtaking him.

After William’s return to Las Vegas, he was treated enthusiastically by the local Indians, and from then on friendliness existed between them. To show this friendly relation, during the second year of the mission an Indian came into the fort one day and informed William II that other Indians were planning to come into the fort on a certain day to get acquainted, with the idea of coming back later to attack the company. Therefore, at the time the Indians came to look things over, the company was engaged in target practice. The display of strength had a definitely discouraging effect on the Indians." -- p. 148

A Bitter Spring Rescue . . . (as told of WCM II by grandson Albert O. Mitchell)

"When Grandfather and his comrades came back, that bitter-cold night of March

23, 1860, from a month in Navajo Country to rescue the body of the son of their

beloved Apostle George A. Smith, he was riding his favorite horse. As the

comrades approached Parowan, near The First Mound west of town, they fired a

volley from their guns to signal their coming. One of the riders fired before

the signal to fire and William's horse, startled, reared, threw up his head, and

felt William's shot between his ears. He fell to his knees and rolled on one of

William's feet. Though neither horse nor rider was hurt seriously, Grandpa, Papa

told us, never got over the mortification of so-abusing a faithful friend!

Young George A. had been treacherously killed by Navajos en route with Jacob Hamblin to a mission among the Moqui.

Jacob describes the danger, both from Navajos and rough, icy terrain. At times, "...the trail ran along the almost perpendicular sides of deep rock fissures, narrow ... where a misstep might plunge us or our animals hundreds of feet below.... On one occasion my pack mule fell, then rolled and slid down to within about a yard of the chasm below."

Hamblin must still have been with William and companions on their return to Parowan, for he took the remains of young George A. to his father in Salt Lake. When Brigham Young offered to pay them for their trip, Jacob replied that no one who had made the trip had made any charge and "...as for myself, I was willing to wait for my pay until the resurrection of the just." --p. 210

General Conference of 1866 -- Bring us back pistols!

"Trouble with Indians was afoot, so William [WCM II] and another brother, a Richard Burton, had asked Richard Benson to purchase pistols for them when in Salt Lake City for Conference in April 1866. At Conference, Richard Benson was called on a mission and was to leave from Salt Lake City directly, so he wrote a letter informing his wife in which he mentioned that he would get the pistol for William or send back William’s money. In her letter of reply, Phoebe Benson wrote,

“William Mitchell is very anxious that you should get the pistols. I think it likely – there will be trouble here this summer [with the Indians]. Two men and a boy have been killed at Salina on the Sevier River.” -- p. 154

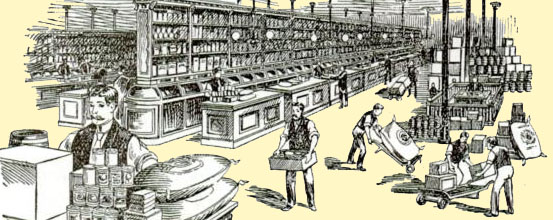

Fort 'Louisa' (i.e. Fort Parowan) . . . boyhood home of WCM III

(see

here for an image of the complete painting, which now hangs in

Brigham Young's office in the Beehive House)

(see

here for an image of the complete painting, which now hangs in

Brigham Young's office in the Beehive House)

"The pioneers who settled Southern Utah had serious troubles with the Indians who made raids on the settlements, drove off horses and cattle, and stole anything they could get their hands on.

In order to protect themselves and their property, the pioneers built a fort. This fort was a quarter of a mile square, built of mud reinforced with straw, cedar and pine boughs. It was 7½ feet thick at the base, 12 feet high and 2½ feet thick at the top, with gates on all four sides wide enough for wagons, other vehicles, and herds of cattle and horses to pass through. The houses were built on the inside next to the wall of the fort which formed one side of the house.

In the center of the fort there was a large public corral where the animals were corralled at night. There were private corrals on the outside of the large corral where the owners could take their cows at milking time. The animals were herded outside of the fort during the daytime to feed. In the northeast and northwest corners of the fort there were towers high above the wall where guards were kept to look over the valley and sound the alarm in case the marauder were seen." --p. 219

"One such alarm was given the night my brother James was born, July 22, 1867. Excitement ran high that night. The Indians were driving the horses and cattle toward a little canyon six miles north of Parowan called Little Creek Canyon. All the men had their horses saddled, and with needed equipment they stood ready to start after the Indians. That night, Mother was so sick that father was unable to go but someone else took his horse, saddle and guns. The settlers caught up with the Indians at the mouth of Little Creek Canyon where a high pitched battle ensued.

It was later said the flash of guns could be seen from the lookout tower at the Fort. The excitement was so great that those who were left with my mother kept the doors open most of the time, expecting they might get news of the battle. My mother caught cold during the birthing and was never well again." --p. 220

"The Pioneers opened the town in a fort. The fort ran a quarter of a mile to the north, a quarter of a mile to the south, a quarter of a mile to the east, and a quarter of a mile to the west. Right in front of our place was the southeast corner.

The grist mill was right in the corner. In each corner was a tower from which guards could look all over the valley to see if there was any disturbance by the Indians. The guards would use spy glasses? — I couldn't tell anything about that. The guards were kept in the towers practically all the time, night and day. There were convenient points and port holes through the walls, where the settlers put their guns out and not open the gates. The wall ran a quarter of a mile west from my place, a quarter of a mile north, a quarter of a mile east and a quarter of a mile south from the place of beginning. The flouring mill was located in the southeast corner of the fort. The creek furnished water power. That was also used as a look-out.

Size of wall? Maybe it would be all right to put it here. The wall is 12 ft. high, 4½ feet through the base, 2½ at the top. It was built of mud reinforced with pine and cedar boughs and stone." -- p. 259

"The Fort was fifty six rods [a rod measures 5½ yards] square [508 yards (roughly a third of a mile) square], divided into ninety-two lots, each two rods wide and four rods deep. A street four rods wide separated the lots from the public corral, which was in the center and occupied ten acres of ground. In the southeast corner of the Fort, a four rod square was reserved for building a log council house.

In the northwest corner of the Fort, a four rod square was reserved for a bastion to command the Fort. There were two big double gates in the center of the walls on the east and on the west. The wall when completed was twelve feet high, seven feet thick at the base, and about three feet at the top. The water was brought under the wall at the southeast corner through a rock culvert and a flume and ran west, then northwest and on out through another culvert to the fields. Each family had room for a garden and some fruit trees back of their house. Some very fine orchards and gardens were in the Public Square even down to the late nineties [1890s]…" p. 73

Of Ol' Shep, and of Bear, Sheep, and Tall Trees on 'The Mammoth'

"In July 1882 [WCM III would have just barely turned 13 years old],

I went on the Mammoth to herd sheep with John C. Dalton (Aunt Huldah’s brother).

We stayed three weeks, which was a very long time to me as I had never been away

from home without my dear father. It was quite a thrilling experience for one

who had never before been away from his family. We went to relieve Sam C.

Mortenson and Marcus L. Guyman who had been there three or four weeks.

They had all kinds of wild stories to tell about the bears they had seen and of

a tall tree they had climbed. I remember one story they told which was

especially thrilling to me. They had run out of food, their horses had left them

and there had been nothing for them to do but walk to town, a distance of

sixteen miles, for food. So after the sheep were bedded down for the night, they

hung a quilt before the cabin door to keep the animals out. Mark Guyman had a

fiddle which he hid in the bedding and while they were gone, the sheep, being

salt hungry, went into the cabin searching for salt. When the men returned, they

were afraid the sheep had destroyed the fiddle. Guyman said that if they had

broken the fiddle, he would have taken his gun and never stopped shooting sheep

until his cartridges were all gone.

All these stories about bears, mountain lions, tall trees, and sheep were

exciting to me and were all so scary for a few days that I hardly dared look

behind myself. We had a good dog, Old Shep, who went with me after water, or

wherever I went, so in time I felt quite at home and could go around without

John at my side." -- p.220

'Paul Revere' rides again! . . . warning of approaching lawmen ( as told by WCM III)

"The U.S. passed a law, known as the Edmunds-Tucker Law, as an ex post facto law prohibiting the practice of polygamy of plural marriage. It was a sad time for our people. Men who had more than one wife were arrested, tried, and given six months’ prison sentences and three hundred dollar fines. I had some thrilling experiences in connection with these times as on occasion I was sent to warn men of the presence of U.S. marshals in town.

One morning, long before daylight, Edgar Clark knocked at my window and asked me to go down to Gavin’s corral, where Ed Dalton and two other men were hiding. They had their horses saddled and left immediately for parts unknown. They didn’t go far, however, as we took them something to eat when we went to the field that day. Another time, Edgar Clark called me out of a crowd and told me to get on Old War Whoop, which was his favorite horse, and go to Paragonah to notify William E. Jones and Stephen S. Barton that the U.S. marshals were after them. Sometime later Edgar Clark also sent me down to Mud Springs and Cedar Bottom to notify Edward M. Dalton, William E. Jones, Lorenzo D. Watson, Stephen S. Barton, Peter M. Jensen and others who were in hiding that the U.S. marshals, with Marshal Ireland in charge, were on their way here to arrest all the polygamists.

The horse I rode was very spirited and I was young, with not much judgment, so when I reached the camp just at nightfall, my horse was wet with sweat. There was no hay in camp so I had to turn him loose to feed. Next morning I found his tracks heading for home. After tracking him all day, without having had anything to eat, I reached home and found him there. However, he caught cold and never recovered from the effects of that trip and soon died." -- p. 222

"Edward Dalton had evaded arrest so many times that these

marshals were especially anxious to effect his arrest. Marshal Thompson of

Beaver swore he would get Ed Dalton, "dead or alive."

So we tried to warn Ed every time danger approached. One morning — when I was

fifteen — Edgar Clark tapped on my window and said, "Will, get on Old Fox and

ride to Cedar Bottoms." When I was ready, he said, "Find Ed Dalton at Mud

Springs and tell him the marshals are in town, laying for him."

I remember riding like the wind across Parowan valley, through the Gap and

bursting out onto Cedar Bottoms. But I didn't reach the Co-op Camp at Mud

Springs; for, as I galloped out of the Gap, I saw three objects flying along the

horizon and across Long Hollow on the Rush Lake Bench. "Ed Dalton!" I thought,

"fleeing from the marshals! I'm too late!"

I spurred Old Fox across the country, trying to come close enough to

investigate, and to see if I could help Ed. On coming closer, I discovered it

was Ed, on Old Brownie; but his pursuers were not lawmen, just Old Brownie's

grown colts, Red Man and Winfield following

their racehorse mother. When I told Ed I had feared the marshals were after him,

he laughed. "And I thought you might be a U.S. Marshal!" And then he laughed

louder. "But don't worry, no marshal — especially after spurring across that

sand as you did — could catch up to Old Brownie's dust!" ....Ed always kept fine

horses." -- p. A-102

"Not long after this, Ed was forced to flee to escape the marshals. He went into Arizona, where he, with Moroni Spillsbury and Aquilla Nebeker, had a mail contract for some time. But Ed soon wearied of hiding away. He wrote to Emily (as he also told Father) that he was tired of hiding and being away from his families. Finally, he came home.

"Let them come and get me. I'm not going to hide any more."

He went about his work, bought a pair of big mules and one day as he, with his son Robbie, was hauling gravel in front of his home (the old William H. Dame home on Main Street, where his and Emily's John now lives), he was approached by William Orton, Deputy U.S. Marshal, of Parowan. The deputy had a warrant for Ed's arrest. When Orton began to read the warrant, he shook so that Ed finally put down his shovel.

"Here, Bill," he offered, "let me read it for you."

He read it to the end, then said, "All right, Bill, I'm your man."

He then handed his shovel to his son. "Here, Robbie, take care of the team. I'll have to go," He waved back, "Take care of your mama."

It should be mentioned that Ed was tending the Co-op sheep herd on Cedar Bottom, camped near Bill Orton's point, at the head of Mud Spring Canyon. His son, Rob, was there with him. Ed went on to Mud Springs to warn the others, while Rob and I stayed to keep the sheep that night. Orton took Ed to the corner north of the Co-op Store and thence to the center of the block northward, where a crowd gathered around. Not knowing what to do with his charge, the deputy left him in custody of the town marshals, Richard Heber Benson and Caesar Callister, whom he deputized for the purpose, while he went to the telegraph office to send a message to the U.S. Marshals at Beaver. (The office was at Charles Adams's and the operator was Robert Quarm.)

There was quite a bit of feeling over this arrest, mostly against the marshals and their helpers. The news quickly spread over town. There was much discussion of the whole affair. On Main Street Ed Dalton joined in, laughing with the crowd. While they were talking, E.L. Clark kept riding up on his famous mare, Hazel, dismounting, then mounting in a hurry and charging away— as if to rehearse the horse for eventualities and to suggest them to Ed. Ed very coolly observed these maneuvers, joked with his custodian, "Well, Heber, I hear you're the fastest man in town!" And all the while he casually and unobtrusively slipped off his boots. Calmly, he tapped Heber on the shoulder, called cheerily, "Goodbye, Heber," and sped off westward down the street north of the Meeting House square. Heber, although a noted runner and doing his best, was not fast enough to prevent his captive's escape. Ed reached the center of the block west of Main Street, then cut across the square to where Edgar Clark awaited him. Hazel had a quick change of riders, and Dalton escaped the marshals again. That night, so they say, Ed sat on his own veranda, strummed a tune on his guitar and sang to his family and friends.

Ed naturally didn't wish to go to trial, but neither did he want to be a fugitive; so he went about his work, hoping he would not be molested. But Orton had sent for Marshal Bill Thompson of Beaver. When Thompson arrived — by night, as usual — and found his prize had escaped, he swore once more to get Dalton "dead or alive." He, therefore, hid his buggy in Orton's straw stack (Orton then lived where Will Rowley now lives, east of the present high school), so no one would know he was in town. He and Orton then waited until morning. They had knowledge that Ed would be driving some cattle westward to Rush Lake, so they hid themselves behind the house of Daniel Page and waited. Page kept a sort of hotel in the west part of town where Thompson lodged.

When Dalton, with Collins Clark and Brigham Brown, came along, driving cattle westward, the marshals cocked their guns. On a sudden, Ed spurred his Red Man around the herd to head them southward. Thompson called out, "Halt!" and at the same time fired. Dalton clutched his horse's mane; Red Man whirled about and Dalton slipped to the ground.

Friends quickly carried him into Page's place, on a door they'd unhinged for a stretcher, then to his father's home — now William Pritchard's place — across the street south of the Meeting House, where he soon died.

Feeling ran high. Some of the young hot-headed friends of Ed Dalton wanted to get at Thompson or even Bill Orton. These two were shut in Orton's house, and an armed patrol stationed around the house. To show how people felt, I might mention that a cattleman by the name of Nutter, who was then in town, rode back and forth in front of Page's (and later Orton's) begging to a swing with his rope at the "assassins." He said he would drag Bill Thompson down Main Street. I remember George Decker and others being very wrought up. "Just let us deal with the d_d stinkers!"

George was a special friend of Dalton's.... Had it not been for the levelheaded intercession of such men as Morgan Richards — "This won't do, boys — the very thing our enemies would like, a hanging" — Thompson might not have escaped with his life." -- p. A-102

Anger at the shooting of Edward Dalton in 1886 by a U.S. Marshall. WCM III rides 'Old Bess' to find and tell his father, WCM II

"I remember the day Ed Dalton was killed, Edgar Clark coming to the old log schoolhouse to fetch Robbie — Robbie who was later to marry my [half-]sister, Maude — and the look on Robbie's face when our teacher told him his papa had been shot.... I don't believe Rob ever got over the shock.

I remember how my father felt about the affair. He was away at the time, on his work as assessor and collector for Iron County. He had left only that morning, going toward Summit.

Aunt Deanie, my father's wife and Dalton's sister, called me to her.

"Will," she said, "get on Old Bess, and ride after your father."

Old Bess was a black mare, quite fleet. I rode her as fast as possible the seven miles up to Summit, where I was told Father had gone on westward. He was past Winn's Hollow, almost to Enoch when I overtook him. When he heard the news, he turned and began to ride sadly homeward. For a long way we rode in silence. Then, all of a sudden, he rose in his saddle, kicked Old Fox to a run, swearing vengeance on the murderer.

"Why, that murdering devil!"

For a few hundred yards he would race wildly. Then, his better judgment and Christian feeling prevailing, he would settle in his saddle and pull Old Fox to a walk. Again we would ride in silence, only once in a while Father would ask a question. Then, his wrath would flare up anew.

"I'll fix that so and so!"

And Old Bess and I could only try to keep up with Fox and Father.

By the time we entered Parowan, Father was cool and reasonable. He helped the leaders to show the few hot-heads that to lynch Thompson would only be playing into the Gentile's hands — for some State and National officials and the marshals were praying for a lynching, so they would have a stronger case against the Mormons." -- p. A-104

"And when Ed Dalton, his brother-in-law, was shot by a U.S. Marshall, in 1886, William grew indignant.... He had just left home, father said, on his round as assessor and tax collector of Iron County when Ed was shot. Grandfather's wife Deanie sent father, then fifteen, on a horse to notify Grandfather. Father caught up to him in Winn's Hollow, near Enoch, ten or eleven miles toward Cedar City.

When Grandfather heard the news, he was shocked -- couldn't believe it. As Father told of the excitement in town, the danger, Grandfather turned Old Fox around and started for home. For a distance, he'd ride wrapped in silence. Then, coming alive, he would lean forward and send Old Fox's sorrel mane flying in the wind.

"I'll fix that so-and-so! I'll ...."

And then, his Christian character prompting him, he would rein in the horse.

"No -- no -- that won't do. We must keep our heads cool."

He would slow Old Fox to a walk, reflecting that our enemies would like us to fly off the handle and commit some act of violence.... But soon, he would jerk rigid, rise in his stirrups and send Fox flying again.

"That dirty rascal! I'll -- I'll have his hide!"...

And so on all the way home." -- p. 202

Note: P. 202 also notes of William Cooke Mitchell (II) that "during the worst oppression, (he) slept with pistol under pillow."

The Saving of Laurette (as told by WCM III)

After Karl was born, April 2, 1908, Laurette began steadily to lose weight. She was quite poorly all the time. Our doctors (Menges Clark and Donald A. McGregor) advised taking her to the mountains to avoid the heat and see if her health would improve.

We moved her with the family up to the Old Ranch, eight miles from Parowan. But she did not improve. Whereas, before, she had weighed 140 pounds – the most she ever weighed – she now went steadily down, until she weighed less than one hundred pounds. Her appetite was very poor; nothing tempted her. As the summer progressed (probably in July), she said she believed that if she could just have some fresh fruit – especially strawberries or raspberries – she could eat them. I often prayed, when about my work or in the night, that some relief would come; that the Lord would make her better. We prayed with Laurette in family prayer, and the children and I prayed in secret.

As we were just desperate to save her life, the children and I set out one morning in frantic search for berries. Although we had seen raspberries on the Mammoth and in the rocks higher up, we did not know there were any around the Ranch. Nevertheless, we scattered out to search the hills and canyons. I sent some of the children over by the First Lake (westward) and Moseman’s Canyon while I with others went down by the Little Pond near the Gum Hill, and thence down east of Bull Flat and around to the north end of the great white cliffs in Main Canyon. Our delight when we finally discovered a lovely patch of luscious raspberries in a little cove can be imagined. Feverishly we picked our shiny two-quart pail full – right up to the rings – and hurried home to Mother.

Note: "Father always felt that the Lord had guided him to find the raspberries and was always humbly grateful to Him. As far as he knew, no one had ever known before that raspberries grew anywhere around the ranch." --p. 281

I remember how thrilled we were to see her eat as though she enjoyed eating! For a few days she seemed a trifle better. But then she began to get worse, until at Doctor Clark’s advice, we moved her back to the Valley, this time to her Mother’s home. There her mother and daughters and sisters and all of us did the best we could to care for her. We had the best medical help available, too. But nothing would restore her, nor check the downward course of her health – not even our great need nor our faith and prayers. Finally, when she sank alarmingly – she now weighed less than eight-five pounds – Doctor Clark, pressed for advice and guidance, said she was in a very serious condition, but he would not like to give a final opinion without consultation with another doctor. As Donald McGregor was then practicing in Beaver (35 miles north-east of Parowan), we sent for him.

I well remember these two doctors calling me out onto Grandma Orton’s porch after their examination. “Will,” they said, “it will be impossible for Laurette to live. She might linger along for another three months, or she might go any time.” As was our custom, we held family prayer for her again. And then I went in to see Laurette. I tried to seem cheerful and tried to comfort her and let her know we all loved her. I tried to let on as if we all expected her to be well soon. And then, with heavy heart, I went up to father’s to tell him. I couldn’t hold up as I told him that my wife was lost.

But father, after I had unburdened myself, said, “Will, don’t feel too bad. The doctors do the best they can. But maybe the Lord will help us. Don’t forget, He knows.” I went out his door feeling as though the end of the world were near. And then, as I passed Will Adams’s gate [papa’s sister, Mabel, was Will Adams’s wife] on my way back to Rette’s mother’s, the thought came to me – the feeling – just as plain as if it had been spoken: “Rette isn’t going to die! She’s going to live. She’s going to get well!”

From there on, I felt as if a weight had been lifted – as if I were walking on air. As I passed Bishop Charles Adams’s gate and was starting across the street to Grandma Orton’s, Don McGregor, who was coming out of Bishop Adams’s, called to me. I stopped and he came and put his arm around me.

"Now, Will,” he said, “you mustn’t feel too bad. Don’t forget you’ve been a good husband to her. You’ve got a wonderful family...“

I said, “She’s not going to die.”

Don looked at me as if he hadn’t heard rightly.

“She’s not going to die,” I repeated.

Again he stared. Then, apparently satisfied that I meant it, he grabbed me and lifted me up like “a bunch of rags” and, laughed. “Of course, she’s not going to die! If you have faith like that, of course, she’s not going to die.”

And she didn’t.

She lived to rear her baby until he was sixteen. She lived to minister to her family, to work in civic and church organizations, to be a comfort and a blessing to her family and friends. And we know that it was the power of God that saved her from death and preserved her to finish her mission here on earth. -- p. 303

The 1918 Flu Epidemic (as told by WCM III)

"During the “flu” epidemic of 1918 our family contracted the disease. There were twelve members of the family sick at one time. No help was available, and I was trying to care for them the best I could. Laurette and Florence seemed to be sicker than any of the others. This disease was sweeping the country and doctors knew very little about it nor how to treat it. At this time, Jake, Flo’s husband, was doing his intern work at the LDS Hospital in Salt Lake, and when Florence took worse we sent for him. However, about the time he arrived she lapsed into a coma. She did weakly acknowledge Jake’s presence before totally losing consciousness. She died on the morning of October 24, 1918, and because of the seriousness of the disease, no funeral could be held, except a short outdoor service. There were many wonderful tributes paid to her and when Brother Morgan Richards offered the dedicatory prayer, he thanked the Lord that these tributes were true. She was buried in the Parowan Cemetery.

There was very little time for mourning, however, as other members of the family were seriously ill. For days, Laurette’s life was despaired of, also baby Virginia was very ill. For a time it seemed as if we were going to lose Laurette as well as Florence. Before Florence died, Walter came over to help administer to them, and after the administration I asked him how he felt and he said that Laurette would live but that Florence would leave us, which is the way it turned out. Jake was brokenhearted at the death of his wife and felt that he was going to lose his baby also. As he sat by the fire holding the baby, I came into the room and spoke to him and the tears ran down his face. I told him not to feel bad, that we would pray to the Lord and tell him our troubles.

Things were pretty discouraging as I was trying to take care of the sick and was behind in all my fall work. We had used all the fuel and the first time I could get away [I] had to go into the hills for a load of wood. I was worn out, lacking sleep, and had to fill a pocket with aspirin to use to keep me going until I could get home. After Mama was better and able to be around a little, Virginia was still very sick. One day I had gone down to the field to get a load of potatoes, and when I came back, ran into the house to see how they all were. The baby was still bad. We all knelt down and asked the Lord to save our little girl. As I arose from my knees a feeling of assurance came over me, and I knew that she would live, which she did and is now married to Roy Allen and has a lovely baby boy of her own." -- p.240

(as told by Mary Ann Mitchell Tolton) "I am sure father had the flu, but by the benevolent mercy of our Heavenly Father, he was able to keep on his feet, and although he was extremely hoarse and had a violent wracking cough, he kept going night and day, giving aid, comfort, food, and blessings to his dear, stricken family . . . This particular afternoon Jake had examined his baby and her lungs showed that pneumonia had set in. He was frantic and went out to the corral to meet daddy, who had just arrived there with a load of potatoes he had hurriedly gathered from the field for the family’s use. With tears running down his face, Jake told father of his fear that Virginia, too, was going to die. Daddy was utterly exhausted from the long, anxious hours of waiting on his loved ones. The deep cough which he had borne up under was almost to wrack him to pieces, and the sorrow and anxiety he had suffered had left him thin, pale, and hollow-eyed. He received the news about Virginia very calmly and told Jake not to “give up,” and added, “We will tell the Lord our troubles.” He unhitched the team and made the horses comfortable, then came to the house, washed himself, put clean clothes on and came into the room where the baby lay feverish and restless and so listless she did not seem to notice those around her. Jake and I were standing sorrowfully by her crib. Father asked us to kneel with him around her crib, and he and Jake laid their hands on her head and father blessed her through the power of the priesthood in him vested. After the prayer, father arose, put his arms around Jake and told him that he had a feeling of assurance that Virginia would live, that he need not feel bad or worry more. From that moment on, she began to improve and by night she was able to take some nourishment, and in a few days was entirely well." -- p.285

Rescue Mission to Panguitch (as told by WCM III)

"After our family had recovered from the “flu” and it was practically gone from our community, the epidemic broke out in Panguitch. There were so many people down with the disease that there was no one left to nurse the sick and take care of the necessary chores inside and out. About fifty or more people from Parowan, both young and old, volunteered to go and help, Marian [Mary Ann] and Ada being among the group who went. At that time I was in the bishopric, and we tried to organize so that the help would be distributed where it was needed most. I made several trips to Panguitch myself, working with the town marshal, Mr. Bell, to help him get help for the ones who were most seriously ill.

One trip, we started with a carload of nurses – volunteers like our girls – and about eleven o’clock at night as we were going up Little Creek Canyon, something went wrong with the car. Sam Halterman, who was driving the car, and I walked back to Paragonah [pronounced Paragoonah]. We got Will Barton to drive us to Parowan where I got L. N. Marsden’s car to finish the trip. When we got back to the car, the girls had gotten out and had built a fire to keep themselves warm and, where the snow had melted around the fire, they were standing in water up to their knees.

On our arrival in Panguitch, we drove to the Cameron Hotel. The town was in darkness as they had no electric lights at that time. There was no light at the hotel, and I had to knock several times before we could raise anyone. Finally, a weak voice answered and asked who it was. I answered it was William Mitchell of Parowan, and [I] had brought more help. She said they were all sick and I’d have to come in and help myself. She told me where to find matches and I made a fire, lit the lamp and found places for people to sleep, then left for home.

The death toll in Panguitch was very heavy from the ravages of the flu, and the people who went from here had many harrowing experiences. Young girls in their teens were nursing the sick and seeing people die. At Pioche, Nevada, the death toll was so heavy that there were hardly enough living to bury the dead. We were indeed thankful when this dread disease left our communities." --p. 241

(as told by Mary Ann Mitchell Tolton) " In a few months after we had recovered from the flu and the townspeople had some respite from it, an epidemic of it broke out in a neighboring town over the mountains to the east of us, in Panguitch. The whole community seemed to contract the disease together. At their call of distress, many of the people of Parowan went to their aid to nurse and care for them, among these were my father, my sister Ada and I. Ada and I went with the first volunteers and father did his work among them a little later. At this particular time father was in the bishopric and was instrumental in obtaining help and conveying this to the greatly distressed people. When Ada and I arrived with the first two carloads of helpers, there were only two men in the whole community available to meet those of us who came to help and to direct us to the homes where aid was most needed. There were no lights because there was no one well enough to run the power plant, no telephone service for the same reason, not half enough doctors to care for the sick and dying.

The town was completely paralyzed. Father took a very active part in bringing doctors, nurses, and other people who volunteered to aid these people. The disease took a frightful toll in death that year, in spite of all the aid they received." -- p. 286