During July of 2025, the Forest Service took public comment on its proposal to restore the Emerald Lake Shelter. Hopefully the shelter will be restored. Historically and culturally, it is an important part of people’s use of the mountain. It also has a role in safety. In August of 2025, the Forest Service announced it had decided to restore the shelter; it does have to allow a certain period for objections. Ideally the Forest Service will move forward with alacrity.

Hiking Mount Timpanogos Safely

Hiking to the top of Mount Timpanogos is a very popular activity in Utah. Mt. Timpanogos is a beautiful mountain, but hikers should know that dozens of people have died on Timp, many of whom were unprepared for what they were getting into. Often, people mistakenly believe that climbing the mountain is simply a matter of walking up the trail, and that if it’s a nice day in the neighborhood it must be a nice day on the summit. This web page suggests that people heading up Timp should first think about how to do so safely. It also emphasizes the need to respect the mountain by having a low impact in the wilderness while visiting there. Then, it describes the main routes to the top, and provides some other information. If you’re curious about what kind of night of fun motivated the creation of this web page, watch this short video:

Safety on Mt. Timpanogos

Take Home Lessons

- If there is any snow on the west side of the mountain, it is too early for most people to hike the summit trails

- Timp is a long, steep, and in places a rugged hike, not an easy walk up

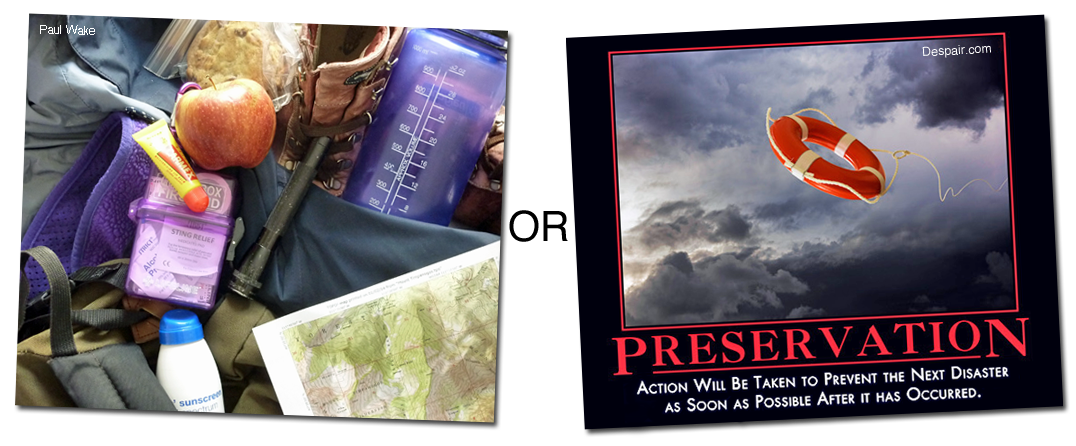

- You need to be in good shape, and you need good footwear, lots of water, sun protection, food, extra clothing for bad weather, a first aid kit with material for blisters and falls and sprains, reliable illumination in case you don’t get down before dark, and a map

- Drive to the mountain early, before parking fills up, and bring your entrance fee

- Fourteen to fifteen miles on this mountain will take most people all day

- The weather on top is colder than in the valley, and afternoon thunderstorms are common along the trails

- Sliding down the glacier is a frequent cause of injuries, and it isn’t fun to hike out when injured

- You do not have to reach the summit to enjoy the mountain

- Always practice “Leave No Trace” ethics while on the mountain—pack out your trash, stay on the trail instead of cutting across switchbacks, and don’t start campfires in the wilderness area

- Here is the most important tip: _______________ (you have to figure this one out for yourself by thinking about how to prepare for and adapt to current conditions)

Preparing for a Safe Hike

Lots of people get themselves into minor trouble on Mount Timpanogos, but most of them limp out and their stories aren’t told publicly. When people get into trouble, it’s often because they weren’t prepared for anything other than ideal conditions. Timp frequently declines to serve up ideal conditions. The best way to stay out of trouble on the mountain is to not assume it will be an easy day hike, but instead to realize it will be a difficult hike, so you should think about what might go wrong, and prepare for it physically, mentally, and materially. Then, as you hike, continue to think about what’s going on, and adapt appropriately to the hazards that present themselves. Far too many people go up the mountain utterly oblivious to the danger they are getting themselves into. There are stupifying levels of cluelessness on the mountain, matched only by a fortuitous amount of dumb luck. Some people cannot even figure out which way to descend because they can’t recognize the trail they came up, and can’t be helped because they do not know the name of the trailhead they left from. Our species would not have progressed much if we only did things we knew how to do, so some bold adventuring is good. However, it remains true that natural selection still functions on Timp, and the mountain can take a toll on more than one’s feet and knees. Be prepared! Timp has been climbed safely over a thousand times by a local retired man, and tens of thousands of other people have summited it, some without incident. Be one of the people who come back with happy stories, not stories of near misses.

Proper preparation includes being in good physical and mental shape; wearing sturdy and comfortable footwear; putting on sun protection; carrying clothing suitable for bad and cold weather even if the morning breaks clear; having a paper map, and knowing how to read it; having a first aid kit, with material for dealing with blisters, cuts and scrapes from falls, and sprains, and knowing how to use it; bringing illumination in case you don’t get down before dark; carrying a lunch and snacks for an entire day on the trail, because it takes a full day for most people to go up and back; and definitely hauling lots of water, or some water and water purification equipment for getting more water from streams. Note that during late summer there may be no streams running anywhere along the upper miles of trail, although there will be water in Emerald Lake. Kleenex, a litter bag, and possibly bug spray might be handy; think through what else you might need. You should also probably let someone know where you’re going, and what they should do if you don’t report back.

Adapting to Conditions and Avoiding Serious Hazards

There are many hazards on the mountain, and they are constantly changing. It is up to you to figure out how to recognize and deal with whatever problems come up during your hike. Pay attention to your surroundings so you will know where you are and where you have come from. Don’t go where the terrain is dangerous, just because you think you’re on an official trail and want to assume it must be safe despite appearances to the contrary. Mind where you step, both to avoid tripping, and to avoid stepping into thin air in places where the trail is eroding away. Don’t cross a snowfield near a waterfall or over a stream, because of the danger of killer snow holes; in fact, be wary of snowfields generally (see “When to Hike” below). Prevent debilitating problems like blisters or dehydration or hypothermia, by wearing the right footwear and clothing, and carrying the right equipment. If you run into stinging nettle, or lightning, or an ornery moose or stubborn mountain goat, or rockfall, work out how to deal with it. Figure it out quickly if it’s a charging moose or falling rock. If it becomes dangerous to continue, turn around. Sliding down the glacier is an outstanding way to get injured, no matter how many people tell you they’ve done it safely. You can choose to slide it, just don’t complain if you hurt yourself. It’s a long way off the mountain when you’re trying to hobble down with injuries. Many of the injuries on Timp happen because of unwise behavior. Behaving foolishly in the wilderness is not a good idea; there is no safety net in the backcountry. Use common sense (which is usually futile advice, since those without common sense routinely confuse certainty with competence). All of this is especially important because rescue is not likely to be immediately available. Even if your batteries hold up, there isn’t cell service on many parts of the mountain, especially along the Timpooneke trail, although you shouldn’t need to call for help because you should usually get yourself out of the situations you get yourself into.

It may be instructive to learn how people die on Timp. Here is a summary of most of the deaths in the past one hundred years; scroll down for additional details in a section below: eleven died from falls, five died from dropping through collapsing snow bridges into holes or from sliding into crevasses, four died from avalanches, four died from snowstorm-induced hypothermia or from late autumn cold, one died from rockfall, five died from heart attacks or other medical conditions, one died from a bear attack, two died from a ski lift accident, one from a zip line accident, two were murdered, four committed suicide, two causes of death were unknown, and seven died from airplane crashes. One thing we learn from these incidents is that it is never good to fly a bomber into the side of the mountain. Other things we learn are to properly outfit yourself for your adventure, and to pay attention to what’s going on around you.

If you fail to adapt to conditions, ye need not abandon all hope. In 1983, with support from the Utah County Sheriff and the U.S. Forest Service, volunteers formed the Timpanogos Emergency Response Team, and on most weekends during the midsummer to early fall there will be a high camp team camping near Hidden Lakes, and spending Saturdays at Emerald Lake with first aid and other emergency supplies, communications equipment, and advice (beginning in 2017, TERT also began stationing someone at Stewart Falls (Stewart Cascades) on summer Saturdays). TERT radio operators at the trailhead shacks both keep in touch with high camp and dispatch, and provide advice to hikers; they camp at the TERT sites in the nearby campgrounds. You are responsible for your own safety while on Timp, but TERT does try to be available to give free help when the mountain gets its heaviest use, and that can cut hours off the time it would otherwise take to get assistance. Don’t hesitate to ask them for help with small things, like blisters or water or directions or wrapping an ankle, because TERT’s whole point is to keep small things small. If Fortune’s wheel does not keep things small, and you are too injured to walk out, the Utah County Sheriff Search and Rescue team can hike up Timp and evacuate you. On the plus side, SAR has a wheeled litter and will carry people down the mountain for free (although if you need an ambulance to the hospital, that will cost you). On the down side, you’re going to hurt for a long time while waiting for SAR to arrive, and the bumpy ride down while being evacuated is especially uncomfortable. Which brings us to medical helicopters. For life threatening conditions, helicopters can legally enter the wilderness, although weather and landing zone availability need to be decent. No one will fly in to give you a ride just because you overextended yourself, though. All in all, it’s best to consciously avoid serious hazards.

Should You Do this Hike at All?

If this hike suddenly sounds unexpectedly challenging, you may wonder if you should do it at all. Yes. So long as you’re prepared, and will refrain from doing anything stupid on the mountain, you should. As Wallace Stegner pointed out, wilderness is “the challenge against which our character as a people was formed.” John Muir urged: “Climb the mountains and get their good tidings. Nature’s peace will flow into you as sunshine flows into trees. The winds will blow their own freshness into you, and the storms their energy, while cares will drop off like autumn leaves.” If things do go bad on the hike, just recall Ed Abbey’s observation that “when the situation is hopeless, there’s nothing to worry about.”

Enjoying Timp Responsibly

Leave No Trace

Much of Mount Timpanogos is a beautiful wilderness area. It does not have unlimited resilience, however, which is one reason why the annual Timp Hike was discontinued—thousands of people hiking at one time was hurting parts of the mountain (another reason was BYU’s concern over drinking and “hoodlumism” in camp). The U.S. Forest Service now limits group sizes on the trails to the summit, to a maximum of fifteen people per group. Even so, tens of thousands of people a year head up the two summit trails. The Forest Service also prohibits campfires within the wilderness, so backpackers need to take stoves instead of building fire pits and tearing down trees. The general rule is: leave no trace. More specifically, don’t litter. Don’t cut across switchbacks—stay on the trail, instead of carving erosion gullies into the mountain. Don’t do anything else that could be on this list of obvious no no’s, like rolling rocks or letting your dog chase baby mountain goats. Scoutmasters and parents, please go over this with your kids before setting out. There is a sad truth about the stay-on-the-trail rule: the trails have so many spots that have worn away to nothing due to no maintenance, and so many areas that get overgrown each year, that people have beat in many side trails and it can be hard to even identify the proper trail. Just do your best to follow the original trail, skipping shortcuts as much as possible. If you want to adopt a higher ethic, then leave the mountain better than you found it—pack out other people’s trash, scatter fire rings, and help maintain what few barriers there are blocking shortcuts across switchbacks.

Let’s recap this one more time: please don’t litter, and please stay on the trail instead of cutting across switchbacks. It’s hard to overemphasize how important it is to leave no trace. Part of the mountainside near Stewart Falls (Stewart Cascades) has been entirely denuded of vegetation, as has part of the area just below Emerald Lake, and those places are now nothing but eroding dirt slopes. Don’t turn more of the mountain into that kind of mess!

There are no toilet facilities past the trailheads. There used to be a toilet in an outhouse off to the side of the Timpooneke trail by where the trail crests into the Timpanogos Basin, complete with a trail sign showing the side path, but the outhouse is completely dilapidated and the toilet is full and foul; ignore the sign and the trail guides that tell you it’s still an option. There is a lesser known open air toilet above Emerald Lake, but it is slowly collapsing in on itself, and it probably would not be enjoyable to be the person to have that plywood finally give way underneath you. Toilet facilities at Emerald Lake Shelter have been gone for decades, and the Forest Service no longer flies toilets in to Hidden Lakes. It does not appear to have occurred to the Forest Service that concentrating impact at a couple of well made toilets might be better for the mountain than the current situation. The Forest Service likes to pretend that by declaring the summit trails part of a wilderness area, they magically become wilderness, but the fact is that Timp is different from any other wilderness area in Utah—the mountain literally abuts the city limits of the towns that most people in Utah County live in, culturally the summit trails are essentially a rugged urban park that is more popular than the parks in the valley, and so at times there may be over two thousand people on the trails at once. It is past time to see the exception to the rule, and return decent toilet facilities to the upper mountain. For now, though, defecate before starting out, avoid urinating near streams, and if you are a backpacker staying on the mountain for awhile and you have to do some business, bury your feces and pack out your toilet paper, or pack it all out. Be aware that above Hidden Lakes or the north edge of Timpanogos Basin there are very few trees to provide privacy, and everything above 10,600 feet is above tree line.

The Forest Service sometimes has a backcountry ranger patrol Timp to encourage good behavior, although the ranger labors under the handicap of not being authorized to shoot people who litter, cut across switchbacks, start fires, or let their dogs off leash.

When and Where to Hike Timp

When to Hike

Hike in the mid to late summer or early fall, depending on conditions (shorter hikes, lower on the mountain, are fine in spring, although in early spring there may be wet trail closures). Unless you are a mountaineer, adept with crampons and an ice axe, it is best to wait until after the snow has cleared from the trails before attempting to hike to the top of Timp. It is dangerous to cross the steep snowfields that can linger into midsummer, because you can slip and then slide rapidly to the rocks below, because you can fall into a moat where the snow melts away from the rock at the edges of the snowfield, and because certain snowfields with runoff flowing beneath them essentially melt from the bottom up, and when they get thin they can break under your weight and drop you a surprising distance into cold snow melt, an experience that tends to be fatal. Snowfields near waterfalls can form into killer snow holes that are particularly dangerous. A rule of thumb is that if you can still see any snow at all on the mountain from the Utah Valley side of Timp, it is too early for most people to safely climb the other, snowier side of the mountain where the summit trails are. One of the best times to hike is when the wildflowers are out, which is late July or early August, depending on conditions. The wildflowers in the upper basins, particularly the Timpanogos Basin, are incredible. This is when summer afternoon thunderstorms pop up, though. The early fall is also quite pretty, but the upper mountain becomes unsafe once it starts snowing on the summit, which is before winter arrives in the valley. Be aware that deer hunting season is in the fall, and—although the webmaster certainly doesn’t oppose hunting for food—there is a subset of hunters who think it appropriate to ignore the rest of the outdoors and hunt on Timp along some of Utah’s busiest trails (in 2016 a couple of them rode up to Emerald Lake on a Saturday when hundreds of hikers were on the upper mountain, and dozens of mountain goats were milling about near the lake, and shot themselves a goat in a display that seemed not to do much for public support of safe hunting). Keep in mind that it can snow on the mountain in any month of the year including in August.

Some people like to do night time hikes to be on the summit at dawn. Be aware that it isn’t always easy to find your way up the trail at night unless you not only have a good light with fresh batteries, but are already familiar with the route. The upper Primrose Cirque switchbacks in particular have a number of false trails that are confusing even in daylight, and there are many spots on both trails where the trail has eroded away and is turning into drop offs. Make good use of your light. It often seems to be a revelation to the local college crowd that a dark, windy, high altitude summit isn’t very warm in just shorts and a cotton t-shirt. Keep in mind that if you’re bellowing songs as you make a midnight climb, every backpacker in every tent on the mountain can hear you.

A handful of people climb Timp in the winter. This is a completely different adventure than day hiking, as it constitutes serious winter mountaineering. For non-alpinists, there are places to snowshoe or cross-country ski on and around the mountain. The Aspen Grove (Mount Timpanogos) trailhead is open all winter, but those thinking of a short excursion up that drainage should keep in mind that avalanches come down into the upper basins and the lower drainage every year (this one at Aspen Grove being an example of how avalanches can run all the way to the campground). This mountain almost delights in massive natural releases. If you’re cross-country skiing or snowshoeing from the trailhead, and you want to go a ways toward First Falls to get away from the snow machines on the road, do not go too far unless you know what you are doing. If you and your friends aren’t carrying avalanche beacons, probes, and shovels, you probably don’t know what you are doing. The same warning applies to backcountry winter travel elsewhere on the mountain, including skiing in from Bear Canyon or the Pine Hollow trailhead and from points east of the Baldy saddle. Take this seriously—in the past quarter century, avalanches have joined falls as the most common causes of fatalities on Timp. Skinning up Timpanogos is fun, but no other mountain in Utah has buried recreationalists so deeply for so many months.

Where to Hike

There are two main ways to hike Timp, the Aspen Grove (Mount Timpanogos) trail, and the Timpooneke trail. Both trails have their virtues, and if you can arrange a shuttle then it might be good to hike up one trail and down the other (but perhaps not on a Saturday or a holiday, due to limited parking). People in Utah Valley are used to seeing Mount Timpanogos as a monolithic wall, but the other side of the mountain, where the main trails are, is delightfully three dimensional. The Aspen Grove (Mount Timpanogos) trail is a bit more scenic but also a bit steeper and more difficult. The Timpooneke trail has a little less elevation gain and may be in better condition, but is a tad longer. Both trails join up in Timpanogos Basin, and the summit trail then crosses a saddle and continues along the western edge of the mountain ridge on up to the summit hut. These trails are each about seven miles long, giving you a round trip to the summit of fourteen plus miles. Some people think the trails are longer; different people’s measurements have yielded results ranging from under six miles to almost ten miles one way. Either trail will take several hours to all day long to complete, perhaps seven to twelve hours round trip for most people. At an elevation of about 11,750 feet (3581 meters), give or take a foot or two or three depending on which source you consult, the summit is almost a mile and a half higher than the valley floor, and it has different weather than the valley. You will be covering almost a mile of that elevation gain on foot. This is the second highest mountain in the Wasatch range, behind Mount Nebo. If you are physically, mentally, and materially prepared, it is a magnificent hike.

Here are some interesting science facts. The higher you climb, the less gravity there is pulling on you, so that may be encouraging. At the Timpanogos summit you’ll weigh less than you did in the valley, albeit just a tiny fraction of 1% less. You’ll be back at normal weight when you return. A difference you will notice is that at the summit the air pressure is lower, so even though the air has the same percentage composition of oxygen as air in the valley, the air at the summit is thinner so there is less oxygen available to you: about 78% of the oxygen that’s available at valley floor air pressure, and only about 66% of what you’d be used to if you came from sea level air pressure. That can sometimes lead to interesting medical problems at altitude. Also, if you want to cook something you’ll find that just as water boils at a lower temperature at the valley floor than at sea level (about 204° F instead of 212° F), at the summit it boils at an even lower temperature: about 191° F.

Aspen Grove Trail (Mount Timpanogos Trail)

From the Provo Canyon side, after turning up the Alpine Loop and traveling for about five miles while passing Sundance and Aspen Grove, you will reach a U.S. Forest Service fee station, and just beyond that is the Theater in the Pines area, which is where you’ll find the trailhead for the Aspen Grove trail (also called the Mount Timpanogos trail). There is also a campground nearby. This trailhead’s parking lot can fill up quickly on Saturdays and holidays during the summer, with hundreds of people heading for the summit, and as many setting out for Stewart Falls (Stewart Cascades). Do not try to get away with parking on the roadway in the no parking areas, or at the BYU Aspen Grove Family Camp, as you may be ticketed or towed. Pay your fee and get to the trailhead early in the morning, before dawn on Saturdays and holidays, which is also important so you can start your hike before the lower trail becomes hot, and so you can finish before dark. Trailhead parking is a problem, and the Forest Service is happy to take your money knowing you won’t have a place to park. There is no cost to use the public road only for travel. For a long time the Forest Service claimed this only applies provided one does not park anywhere. Actually, it was not legal for the Forest Service to charge a fee for parking along most parts of the loop, see 16 USC 6802. In its 2018 American Fork Canyon visitor’s newsletter the Forest Service finally acknowledged that entrance stations passes aren’t required everywhere, but it left up signage claiming that paying a fee is required for stopping along the loop. Regarding parking at the trailheads, perhaps you could decline to pay at the fee station, and then do the self-service payment in the parking lot if you find a space. If you drive across the top of the Alpine Loop, don’t assume the “Summit” trailhead has a trail to the summit; that’s the “summit” of the loop road, and there are nice trails there, but there isn’t any official mountain summit trail leaving from that trailhead.

From the parking lot just past the fee station, the Aspen Grove (Mount Timpanogos) trail is toward the right side of the parking lot as you look uphill; the trail near the pit toilets is to Stewart Falls (Stewart Cascades). In 2016 the Forest Service did put in some small signs to point this out (after putting up a large sign on the importance of paying your fee). If you don’t see the TERT trailhead shack just after crossing the meadow and getting into the trees, you’re on the wrong trail. The Aspen Grove (Mount Timpanogos) trail heads westward up the drainage to First Falls, which is also called Timpanogos Falls, and the trail was once paved as far as Second Falls, but that mile and a quarter of pavement is being left to deteriorate. That section of trail makes for a short day hike by itself, as an alternative to the Stewart Falls (Stewart Cascades) trail. Before you get to First Falls, and just before reaching the wilderness boundary, Lame Horse trail will veer away to the right; mind the sign, and take the summit trail to the left. The trail switchbacks up the north side of the drainage from First Falls to above Second Falls, on up to one very long switchback sometimes called the Heber switchback, before traversing a talus slope (a rockslide) below the Primrose Cirque headwall and then switchbacking way up a steep section of the southwest part of the cirque and finally flattening out a bit in the Hidden Lakes area. The switchbacks above First Falls have many spots where the trail veers out just a bit from what would seem like a straight path, and dips down and then up; these are spots where the trail did go straight at a constant grade, but the Forest Service did not repair slumping trail and now erosion is changing the very course of the trail. The switchbacks in upper Primrose Cirque have a number of false trails that can be confusing. If after crossing the big talus slope you soon come to a waterfall, you have missed the first group of switchbacks. Be careful up high on the third group of switchbacks, because if you miss one particular switchback you will quickly be on dangerous ground, and even on the proper trail there is a short bit of rounded over rock that makes for hazardous footing. From Hidden Lakes the trail winds upward toward Emerald Lake, which is at the top of a short but steep hill; a now eroded path has been beaten into that hill straight upward so that the trail no longer switchbacks to the north as it once did. This five plus miles is enough of a hike for some people, and the area around the Emerald Lake Shelter is a popular resting spot where hikers contemplate the distance to the summit rising high overhead. In days of yore the local community rallied to build the shelter, but more recently the U.S. Forest Service failed to maintain the historic shelter despite promising to do so, and when the shelter largely collapsed in the 2022 the Forest Service refused to restore it. The shelter itself provided some refuge from storms, although it could get cold in there. If you are backpacking, please don’t camp on the “island” in Emerald Lake, or anywhere next to water, unless you want a visit from the backcountry ranger. For those continuing to the summit, the trail veers to the northwest and crosses a low ridge into Timpanogos Basin. From there almost everyone heads directly toward the saddle—the col—on the ridge to the west by cutting across the north facing slope on a beat in trail that is more or less passable, although there is a section with rocks that are are unstable underfoot, snow lingers late into the summer above a cliff band, and the last push up toward the saddle is steep with little traction on the dirt. It is also possible to drop into Timpanogos Basin and hike the original trail through the flowers to the other side to join the Timpooneke trail and climb to the saddle from there, but that adds a mile and a half. The saddle is another popular resting spot as hikers both enjoy the view of Utah Valley, and ponder a final section of trail that is less than a mile long but seems a lot like the stairs of Cirith Ungol. From the saddle the trail works southward up the west upper edge of the ridge to the summit. There is a summit hut there (originally called the “glass house”), although it does not offer much shelter. Below some ledges there is a very long drop down the east side of the summit; a fall there is best avoided. Instead of returning to the saddle and Timpanogos Basin, some people work their way further south and then glissade northward down the glacier from the glacier saddle to Emerald Lake, but that is not particularly safe. Note that although in some years there is enough snow there to hold ski races, in some other years the above ground glacier is mostly gone. One year in the nineties a crevasse temporarily opened in the rock, down through buried ice.

Timpooneke Trail

From the American Fork Canyon side, traveling up the Alpine Loop after paying at the U.S. Forest Service fee station near the mouth of the canyon, and a ways after passing both the Timpanogos Cave National Monument and the turnoff to Tibble Fork (North Fork), the Timpooneke trailhead is by a parking lot in the Timpooneke campground, which is up a little side road that turns off about eight miles past the fee station. This parking lot too can quickly fill up on busy Saturdays and holidays, so the same cautions mentioned above in the Aspen Grove (Mount Timpanogos) section apply to parking at the Timpooneke trailhead. In July of 2023 the Forest Service announced a plan to require people parking at the Timpooneke trailhead on Saturday, Sunday, or holiday mornings to reserve a parking pass online. This will catch a lot of people by surprise. And it will more than double the cost to hike the Timpooneke trail. There is a web page for making a parking reservation. There is very limited overflow parking in marked turnouts along the Alpine Loop near the turnoff to the Timpooneke campground, if one’s vehicle can be parked completely off the pavement. The Timpooneke trail gets some equestrian use, so give people room if they’re unloading horses from a trailer at the trailhead instead of from over in the equestrian area. While hiking, don’t run up on a horse from behind, and if a horse approaches on the trail you should step off the trail—ideally to the downhill side—and quietly talk to the rider so the horse will know you’re there and are human. You can pronounce Timpooneke any way you like. Many people say it something like Timp-a-nookie, but that doesn’t seem like how it’s spelled, as the Tim-poo-knee-key adherents will tell you either politely or with some exasperation.

There is more than one trail leaving this trailhead, so look for the TERT shack. From there the Timpooneke trail heads southward through evergreens up the drainage, crossing the wilderness boundary almost immediately. A little over a mile up the trail, where the trail turns west, there is a short spur trail going east to the Scout Falls viewpoint, which is not always signed. Some people hike just that far as a day hike, although trees and vegetation are gradually obscuring the view. The trail then winds through a number of flatter almost meadowlike areas each a giant step above the other, climbs up the west side of the drainage, rising further up the Giant Staircase as it crosses a talus slope, then switchbacks higher yet, crossing a wall toward the rocky upper east side of the drainage, and then climbs up into Timpanogos Basin at a bit under five miles. In Timpanogos Basin, a short way past the old toilet trail, the Timpooneke trail will split, with the left trail going to Emerald Lake and the right trail climbing to a junction with the Aspen Grove (Mount Timpanogos) shortcut from Emerald Lake, just below the saddle. Unless you’re out of water and need to head to Emerald Lake with your pump or chemicals, or you want to take a walk into the basin to see the flowers, take the right trail, up the west side of the basin, and be careful because there are spots with a steep drop off where the trail has eroded away due to inadequate maintenance. If you do detour to Emerald Lake and then take the direct route from there to the saddle, you’ll add about three quarters of a mile to your hike. After crossing the saddle, the trail heads southward for the final climb to the summit. A few people turn off at the old toilet trail when they reach the beginning of Timpanogos Basin, and from a smaller basin to the west work up the ledges to the northwest to find the wreckage of a B-25 bomber that crashed there; that requires off trail route finding on difficult, isolated terrain. What’s left is at N 40° 24.4336′ W 111° 39.3225′ (the lower site) and N 40° 24.4062′ W 111° 39.4034′ (the bottom of the upper site, with flattened wreckage spread further up the slope above).

Other Things to Do

Remember that there is more to do on the mountain than just climbing to the summit. For example, you can hike to Stewart Falls (Stewart Cascades), take a tour of Timpanogos Cave, walk the boardwalk trails at Cascade Springs, explore a lesser known peak or trail on the massif, study the ruins of Utah War defensive structures or other historical sites or attend a cultural event, go camping or backpacking or horsepacking, get a nature guidebook and learn firsthand about the geology and biology of the area, do a service project, play on or picnic by one of the rivers that borders Timp, drive the Alpine Loop during the fall, or enjoy winter activities such as downhill skiing at Sundance or going cross-country skiing or snowshoeing. Just treat the mountain well. Whatever your activity, be careful driving home. It’s dangerous once you’re out of the woods.

If you do any ten of the above twelve activities, you can join the ranks of the Grand Order of Admirers of Timpanogos. It might not be quite the same as joining the illustrious pantheon of Timp hiking worthies: Stewart, Roberts, Hart, Pace, Kelsey, Hilton, Heaton, Kearney, Meyer, Ashcraft, Woolsey, Lowry, and others. However, by self-awarding yourself membership in the Order, you can do exciting things like printing the graphic on the right onto sticker paper, and pasting it on your forehead or Timp map or anything else that strikes your fancy. Not many people do that!

If you do any ten of the above twelve activities, you can join the ranks of the Grand Order of Admirers of Timpanogos. It might not be quite the same as joining the illustrious pantheon of Timp hiking worthies: Stewart, Roberts, Hart, Pace, Kelsey, Hilton, Heaton, Kearney, Meyer, Ashcraft, Woolsey, Lowry, and others. However, by self-awarding yourself membership in the Order, you can do exciting things like printing the graphic on the right onto sticker paper, and pasting it on your forehead or Timp map or anything else that strikes your fancy. Not many people do that!

In doing any of these things, remember the importance of prudence. Apart from the summit trails, Stewart Falls (Stewart Cascades) is one of two places in Utah County—the other being Bridal Veil Falls—that are hot spots for injury due to the large number of people going there unprepared while assuming they will have an easy and safe walk. This results in lots of relatively minor injuries, and sometimes in more serious injuries or in deaths from leaving the trail and falling, because multitudes are unable to grasp the wisdom of staying off steep, sketchy places. Exploring remote or steep areas involves an increased risk of being removed from the gene pool. When engaging in wholesome recreational activities near the rivers, be mindful of the drowning danger, especially during spring runoff. It’s somewhat safe to float Provo River from Deer Creek Dam to Vivian Park if wearing a PFD, but even stepping into the river near Bridal Veil Falls at spring flood would be unwise. So very unwise. Don’t drive the Alpine Loop with a trailer or an RV, as it’s a narrow and twisty road in the middle part. Winter backcountry travel entails serious avalanche danger, which demands competent avalanche terrain reading ability and well practiced companion rescue skills.

If you want to do something really amazing, and you're a strong hiker with ties to a nonprofit or governmental or university group that will back you up and can claim some interest in Timp, try to get Google to let you carry their Trekker along both trails to photograph them. That still hasn't happened.

Maps of Mount Timpanogos

The map on the left below shows how to get to the trailheads. You can approach the Alpine Loop from Highway 189 on the south side, or Highway 92 on the north side of Utah County. In Provo, Highway 189 is University Avenue, which goes to Provo Canyon; you can also reach Provo Canyon from Highway 52, 800 North, in Orem. From the Thanksgiving Point area, Highway 92 is the Timpanogos Highway through Highland, which goes to American Fork Canyon; you can also reach the mouth of American Fork Canyon by going up North County Boulevard, Highway 129, the bottom of which can be reached from Pleasant Grove Boulevard, to Highway 92, or by following Highway 146, 100 East in Pleasant Grove, which becomes North Canyon Road and travels along the base of the mountain to Highway 92. From the east, take Highway 189 from Heber. In the wintertime the Alpine Loop is closed between Aspen Grove on the Provo Canyon side, and a short way above the Tibble Fork (North Fork) turnoff on the American Fork Canyon side, at Pine Hollow. The satellite image on the right shows how in the early summer there will be little snow showing on the Utah Valley side of the mountain, and the trailheads will be green and warm, with birds singing and creeks burbling. However, the bowls of the upper mountain will still be in the grip of the White Witch. Click either map for a larger view.

The topographical map below shows the general route of the summit trails. You can click on it to get a printable version good for portable use. Although you likely can follow the trails without a map, having one gives you a better perspective on your progress up the mountain. Frankly, advocating use of a map also involves an ulterior motive: it is another way of suggesting that hiking Timp needs to be treated as an excursion into the backcountry. The webmaster has a Timpanogos Emergency Response Team-specific map too, but it is cluttered with labels and probably not as useful as the one below.

This panoramic overview of the mountain was digitally created in 2024, and its creator released it to the public domain, so it’s accessible to all.

Photos of Timp’s Summit Trails

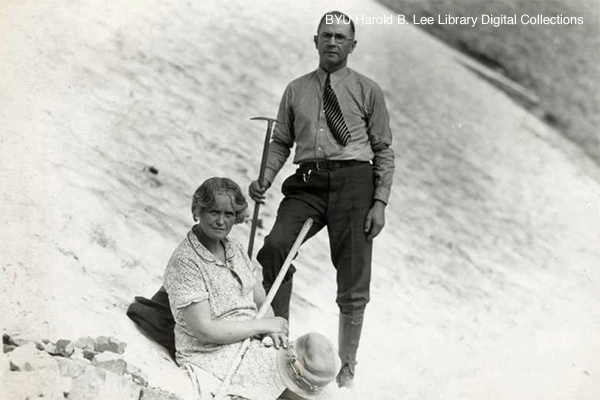

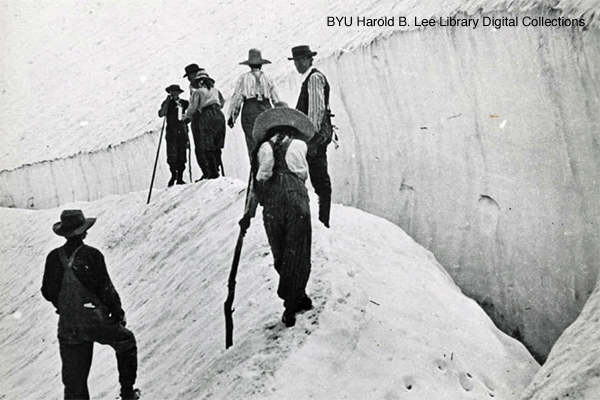

Climbing the glacier in 1907, and exploring what appears to be a small crevasse below a large crown fracture.

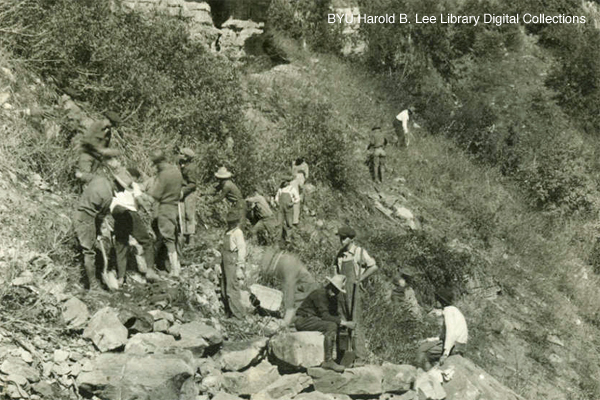

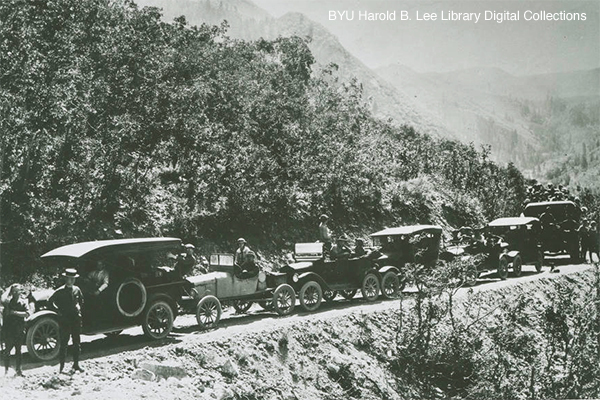

The early Timp Hikes required getting up to Stewart’s Flat (now Sundance) on a Friday and camping, then following sheep trails and bushwhacking the next day up to the summit, then going back to the valley on the third day. Early Timp Hikes went up the glacier, sometimes with a fixed rope for aid.

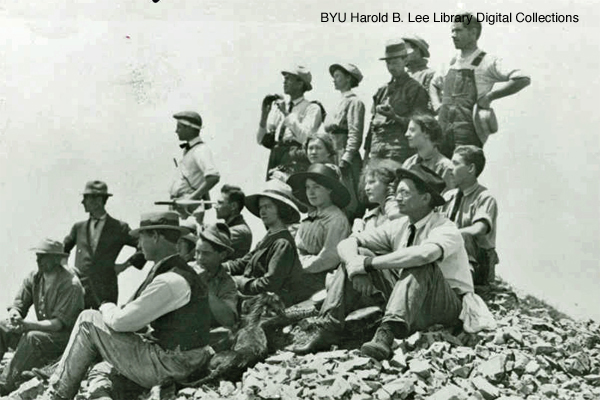

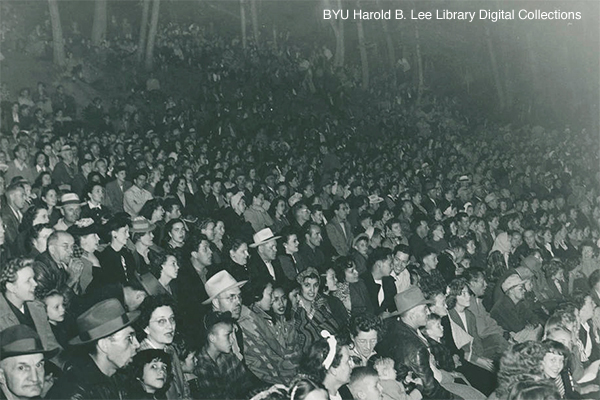

The annual Timp Hike grew to have a prehike bonfire and program. The community treasured their mountain playground, and added resources to the mountain such as the Emerald Lake Shelter to improve access to the summit.

The meadow at the Aspen Grove (Mount Timpanogos) trailhead. The trail starts to the right. The trail on the left side of the meadow, by the pit toilets, is to Stewart Falls (Stewart Cascades), a family day hike (mind the stinging nettle). In this springtime photo there is too much snow on the upper mountain to safely hike to the summit. In the wintertime, avalanches have buried a number of people in this valley.

Timp in autumn, at Aspen Grove. Up at the summit, it’s already winter. (The peak in the center left is not the summit, it’s Roberts Horn.)

Timpanogos Emergency Response Team shack about a hundred yards up from the Aspen Grove (Mount Timpanogos) trailhead. Sign the register, and chat about trail conditions and summit weather. If you’re starting as early as you’ll need to if you want to find parking on a Saturday or a holiday, the volunteer might not be up yet, though.

First Falls, also called Timpanogos Falls, is about a mile up the Aspen Grove (Mount Timpanogos) trail. In past decades, most of the falls and ledges had now largely forgotten names.

Second Falls is about a quarter of a mile past First Falls, and it is where what’s left of the old pavement ends. This is also where Lower Killer Snow Hole forms in the spring and early summer. The sheriff used to blast the snow in the spring to save lives. Always presume that snowfields near waterfalls are particularly dangerous.

After traversing the rocky slope visible in the center right of the photo, the trail switchbacks up to the top of Primrose Cirque through the green area in the center left. In the spring, Upper Killer Snow Hole forms at a spot most of the way up the switchbacks. Wait until mid summer to hike here, and then please stay on the trail, instead of making worse the erosion producing shortcuts across switchbacks.

Hidden Lakes is a popular camping area for backpackers. It was especially popular when there were toilets here, but the Forest Service no longer maintains toilets in the wilderness area. The trail is by the crescent of trees on the left of this photo, which was taken from above.

This is the Emerald Lake Shelter, a historic structure and an important refuge on the upper mountain. Forest Service malfeasance allowed it to collapse in 2022. The white summit hut is barely visible far above, with a cloud behind it.

There is a large, flat area at the saddle that makes for a popular resting place and viewpoint. All these good people are packing out their own litter.

TERT shack near the Timpooneke trailhead. More than one trail leaves from the same trailhead. For the Timp summit, take the trail that goes by this shack.

A typical TERT high camp team, at the Emerald Lake Shelter on a Saturday: a team leader and assistant leader, an amateur radio operator, and medical personnel, all volunteers.

SAR training at Aspen Grove. SAR does have a bad habit of clogging trailheads and keeping them clogged. On the upside, they provide a lot of service for free.

Links to Other Sites about Mt. Timpanogos

You would think the U.S. Forest Service would have put a decent amount of information online about the summit trails, but it hasn’t. It has not even done a very good job with trailhead information, a largely pointless sign it put up in 2018 being a prime example (photo at left), and when you hike past the plaque on a rock near the Aspen Grove trailhead you may notice that much of the information on that plaque is inaccurate. It’s no secret that they would rather limit use than facilitate it. They even keep talking about a possible permit system. Timp is a cultural treasure that should not be subjected to a permit system. Avoiding such an abomination is in part a responsibility of hikers, who need to stop littering and stop shortcutting across switchbacks, which only encourages the feds to try to lock up our mountain. If you happen to meet any officials from the Pleasant Grove Ranger District of the Uinta-Wasatch-Cache National Forest, please tell them that the Forest Service should do more than token maintenance, and should rebuild the missing parts of the trails (it’s not as if they don’t have entrance fees flooding in that should be used for that), and also should restore the historic Emerald Lake Shelter. Washington’s Green Mountain Lookout in the Glacier Peaks Wilderness was preserved; our Emerald Lake Shelter should be also. Sadly, but utterly predictably, despite having promised to begin restoration in 2016, the Forest Service did nothing, and in 2022 the shelter largely collapsed.

You would think the U.S. Forest Service would have put a decent amount of information online about the summit trails, but it hasn’t. It has not even done a very good job with trailhead information, a largely pointless sign it put up in 2018 being a prime example (photo at left), and when you hike past the plaque on a rock near the Aspen Grove trailhead you may notice that much of the information on that plaque is inaccurate. It’s no secret that they would rather limit use than facilitate it. They even keep talking about a possible permit system. Timp is a cultural treasure that should not be subjected to a permit system. Avoiding such an abomination is in part a responsibility of hikers, who need to stop littering and stop shortcutting across switchbacks, which only encourages the feds to try to lock up our mountain. If you happen to meet any officials from the Pleasant Grove Ranger District of the Uinta-Wasatch-Cache National Forest, please tell them that the Forest Service should do more than token maintenance, and should rebuild the missing parts of the trails (it’s not as if they don’t have entrance fees flooding in that should be used for that), and also should restore the historic Emerald Lake Shelter. Washington’s Green Mountain Lookout in the Glacier Peaks Wilderness was preserved; our Emerald Lake Shelter should be also. Sadly, but utterly predictably, despite having promised to begin restoration in 2016, the Forest Service did nothing, and in 2022 the shelter largely collapsed.

- Mount Timpanogos Trail (Aspen Grove Trail) #052

- Timpooneke Trail #053

- Timpanogos Summit Trail #054

- Wildflower Identification

- Rocky Mountain Bighorn Sheep and Mountain Goats

Leave No Trace

Leave No Trace- Pins! (it looks as if the Leave No Trace pins program has ended; by way of shameless bragging, the webmaster’s eldest daughter was the first member of the public to earn the Timp pin, and the first to earn all of the Uinta-Wasatch-Cache National Forest wilderness pins)

The Timpanogos Emergency Response Team used to occasionally provide online weather and trail condition updates directly from the mountain, but its web site is more useful for background information on hiking Timp.

Michael Kelsey wrote the closest to definitive book about Mt. Timpanogos, but it went out of print. One day the webmaster chatted with him in Provo, and wondered if he’d be doing another edition. No, not at that point. But then in late 2019 he released a second edition, which is listed below. As with all of Mr. Kelsey’s guidebooks, the route maps and descriptions are approximate and assume you are able to do route finding on your own with only general pointers as to where to go, and his estimates of trip length and difficulty are quite optimistic for most hikers. There is a lot of interesting historical information in the book, in addition to suggestions for many lesser known hiking routes (some of which are quite dangerous). The other two books listed here are an interesting history by Jared Farmer (“Here is the creation story of a landmark—one beloved peak in the American West. In the beginning, this mount had form without meaning. It was not visible, nor haunted; now it is both. Getting to the bottom of the matter requires disorientation. The bedrock is liquid. The landmark’s life history beings with the ghost of a lake.”), and a coffee table book of Willie Holdman photography.

- Hiking and Climbing Utah’s Mt. Timpanogos (first edition was titled Climbing and Exploring Utah’s Mt. Timpanogos)

- On Zion’s Mount: Mormons, Indians, and the American Landscape (and a review)

- Timpanogos

Summitpost.org has a lot of online information on climbing Timp.

- Climbing Mount Timpanogos

- Aspen Grove Trail

- Timpooneke Trail

- A Little Known Trail

- Northern, central, and southern maps of parts of the mountain (many of these routes are definitely not for casual hiking or easy winter backcountry skiing)

Some other online hiking guides.

- Hiking at Your Own Pace

- Your Hike Guide

- Climb Utah

- Timpooneke Trail Guide (lots of photos)

- Lots of photos here also (mostly Timpooneke)

- Enjoying the Ups and Downs (starts at 0:52)

A couple of good general books on hiking and backpacking.

Weather stations.

- Summit Weather Guess (oddly, it’s a mix of Provo conditions and an often inaccurate mountaintop forecast)

- Aspen Grove UDOT Weather Station (this is not the weather at the summit, it’s at one of the trailheads)

- Timpanogos Divide Snotel Station (this isn’t summit weather either, just mid mountain weather from near the top of the Alpine Loop)

- A BYU Webcam

- Sundance Webcams

If you’re going up the mountain in the winter, know the snow.

- Utah Avalanche Center

- KBYG and a very useful video

- Avalanche Classes Here and Here (sadly, Avy 1 does not teach the “hopping” method of avalanche survival)

- NARSID (a lesser risk in Utah, but still worth being aware of)

The history and geology of Mt. Timpanogos is fascinating. Regarding history, Timpanogos Basin used to be called Big Hole, Hidden Lakes used to be called Spring Lakes, Primrose Cirque used to be called Little Provo Hole, and Big Provo Cirque used to be called Big Provo Hole, and all of the waterfalls on the Aspen Grove side were named.

- Geology, History, and Other Information, and Another Overview Article

- One, Two, Three, and Four Web Pages on the Provo Canyon Guard Quarters

- The Tunnel Through the Mountain

- An Epic Tale (this route probably went up either what is now called “Everest Ridge,” which got its name later when the Utah Doug Hansen and his team used it to train for their attempt on Mount Everest, or went up a route a bit to the south of that above Dry Canyon; don’t try this at home—at nearly the same time in 2016 that this story was posted on the state’s history web site, a party climbing in this area had a member buried in an avalanche)

- History of the Annual Timp Hike (scroll down)

- The Treasure Trove of Annual Timp Hike History

- The Story of How Hiking Timp Became Popular

- The Legend of Timpanogos

- “Timpanogos, Wonder Mountain”

- The Demise of the Annual Timp Hike

- Remembering the Annual Timp Hike

- History of the Summit Hut

- Information on TERT’s Early Days and on More Recent Days

- Conflicting Views on the Aspen Grove Trail Route (this now largely overgrown trail segment goes up through the “Primrose” printed on the topo map below, between the lower and upper parts of the long switchback often called the “Heber switchback,” continuing the existing switchbacks above First and Second Falls in a logical manner, without the need for the newer long switchback with its accompanying small snowfield)

- One Take on Whether the Glacier Is a Glacier

- Another Take on Whether the Glacier Is a Glacier (probably from people who say Pluto isn’t a planet)

Wikipedia has an entry on Mount Timpanogos.

Hall of the mountain kings.

Wilderness medicine.

- Altitude Air Pressure Calculator (see how much oxygen you’ll find at the summit; remember that the cure for altitude sickness is descent), and Information on Altitude Problems

- A Good Example of a Wilderness Medicine Patient Assessment, as well as other NOLS videos on wilderness medicine.

- Assorted Tips on Wilderness Medicine and More Resources, from NOLS

- Utah EMS Information on Patient Assessment (pages 5–12)

- Utah EMS protocol guidelines; some of this is relevant in the wilderness

- A Good Lecture on Backcountry Trauma and Improvisation and the lecture’s slides

- A Bunch of Videos on Wilderness Medicine, and on non-wilderness medicine specific videos on Trauma Care, Spinal Injury, Bites and Stings, Marine Life Toxinology, and Shrooms

- Blister Prevention and Care, and Part 1 and Part 2 of an article about blisters, and a video about blisters

- Dealing With Ticks (there are definitely ticks on Timp, although most hikers don’t pick one up)

- Wound Care, and Improvised Irrigation at Its Finest (scroll to Figure 7)

- Ottawa Ankle Rules and Wrapping a Sprained Ankle and Taping a Sprained Ankle

- Guidelines for Wilderness First Aid and Wilderness First Responder Scope of Practice Background Information and Wilderness Medicine Field Protocols

- A list of links to some detailed Wilderness Medicine Practice Guidelines from the Wilderness Medical Society

- Information on the National Ski Patrol’s Outdoor Emergency Care (OEC) Standards

- CPR Guidelines, and the Definitive CPR Video

- CPR in Space, Wilderness Medicine in Space, and Emergency Medicine in Space

- Dangerous Bee Stings May Become More Common

- Shoulder Dislocation Reduction Techniques (including the Snowbird Technique), a Self-reduction Technique, another List of Shoulder Dislocation Reduction Techniques, and a List with Links to Videos (not a common injury on Timp, but of interest to the webmaster)

- Everything You Need in a First Aid Kit (if you already know what you’ve needed in the past and how to use it, you probably already know what you need in the future, and you can improvise anything else by using your brain instead of carrying a first aid kit made by someone else and full of things you’ve never seen before, although if you really need to buy a kit there are sources here and there, but practice on yourself before using this stuff on someone else)

- Why Mosquito Bites Itch

- Already Know Why Mosquito Bites Itch, But Want to See What Else You Know? Want to Try Another Test?

- Landing Zone Tips; for more information on serious troubles with the non-hospital medical helicopter industry, here is an interesting article

- Outdated and Unapproved Burn Treatment (from 1:42-2:12)

- NEXUS Low Risk Criteria and Canadian C-Spine Rule for cervical spine assessment

- Want to Learn to Be a Rescue Hero? Want More Options? And Still More? And This Good One? (these courses will give you a pretty card that you can show to injuries if you think it will heal them, but only experience will take you from giving bumbling care to providing helpful care—this means you, WFRs and paper EMTs: primum non nocere!); want a more critical view?

- AWLS and DMM training

- Map of Bear Attack Hazard Areas and Things to Say to a Bear

- Auerback book, Forgey book, NOLS book, Hypothermia book, Wilkerson book, The Mountaineers book, Tilton book

- Volcano Rescue (sort of)

- Drones

- Stinging Nettle exists here and there on Timp, but an interesting thing is that there is sometimes lamb's ear nearby, and the soft leaves can help with the irritation.

Odds and ends.

- The Parable of the Ten Hikers

- Different Types of Fun Offered by Mount Timpanogos (all available on the two main trails)

- The Ten Essentials (Kleenex and a litter bag ought to be mentioned here somewhere, and perhaps insect repellent)

- Thoughts on Hiking and Thoughts on Camping and Thoughts on Cross Country Skiing

- Guide for the Aged: Avoiding Unnecessary Suffering While Backpacking Timp

- A Nod to the Amateur Radio People Who Helped the Webmaster—KG7JZJ—Get Licensed (having a radio eases the webmaster’s mind a bit on the Giant Staircase stress test)

- Girl Talk: Peeing in the Backcountry (or read Kathleen Meyer’s naughtily named book; this poop page is good too), and Girl Talk Part 2: Handling Your Period in the Backcountry

- Timpanogos Emergency Response Dive Squad

- Will You Go to Hell If You Litter and Cut Across Switchbacks? (well, it seems likely that the Almighty gets quite perturbed by those things)

- The Hayduke Trail, the Pacific Crest Trail, and the Oregon Coast Trail (other great hikes in the western United States)

- A Handful of SAR Links Not Related to Timp

Fatalities on Mount Timpanogos

Here is the breakdown, mentioned above, of many of the fatalities on Timp; most of this information comes from Kelsey’s book and from newspaper stories, and some comes from American Alpine Journal and Utah Avalanche Center and National Park Service reports (this list does not include things like traffic accidents, deaths in homes, drownings in the Provo River or American Fork River, or any of the other deaths in the bottom of or across Provo Canyon or American Fork Canyon):

- In 1937, a fifty three year old Ohio man on the annual Timp Hike died of a heart attack near the top of the glacier, despite efforts by Boy Scouts and doctors to resuscitate him.

- In 1943, three local men aged thirty one, thirty one, and thirty two died when they were caught in a snowstorm while deer hunting up on the mountain near the north end of Roberts Ridge, after having left their winter gear in their trucks because the weather was initially good; a fourth man was brought down alive.

- In 1946, a thirty nine year old man who had gone to the Stewart’s Flat area alone to teach himself to ski was found dead of a heart attack.

- In 1954, a nineteen year old woman from Provo died on the annual Timp Hike when she was struck on the head by rockfall from the cliff above where she was descending the glacier.

- In 1955, five men died—a twenty two year old Air Force engineer, a twenty five year old Air Force co-pilot, a thirty year old civilian employee of the Air Force, a thirty three year old pilot, and a forty five year old civilian employee of the Air Force—when their B-25 Mitchell medium bomber crashed into the side of the mountain above Timpanogos Basin while flying in bad weather from Montana to California.

- In 1961, a forty five year old man died when a Cessna 172 from California, in which he was a passenger, crashed into trees on the mountain near the top of the Alpine Loop; the pilot, who had dropped through clouds and unexpectedly discovered he was quite close to the mountain, survived his many injuries despite being trapped in the wreckage for days in winter weather.

- In 1964, a nine year old Orem boy on the annual Timp Hike died after falling from the east side of the summit onto ledges below (he did not fall all the way down the cliff face), either because wind gusts blew him over as he was close to the edge, or because a dog nudged him; despite a rescue effort by people on the mountain who downclimbed through continuous rockfall caused by spectators, and by a helicopter pilot flying up through difficult winds, the boy’s injuries proved too severe to survive.

- In 1966, a thirteen year old girl and a forty nine year old woman from Provo died when they fell from a malfunctioning ski lift at the Timp Haven Resort.

- In 1969 or thereabouts, a hiker who decades later told this webmaster about it saw resuscitation being attempted on a man whose body was laying on Couch Rock/Cardiac Rock.

- In 1969, a sixteen year old boy from Murray adventuring on his own in the East Peak/Elk Point area, fell and died; his body was located a week later.

- In 1972, a sixteen year old girl and a seventeen year old girl, both from Utah County, were raped and murdered at the Aspen Grove trailhead by someone who had recently been released from a mental hospital.

- In 1975, a twenty six year old Provo man died when, while walking the Timpanogos Cave trail, he decided to try to climb a nearby cliff without gear, and fell.

- In 1978, a thirty six year old man from Idaho, returning from a trip to Colorado, flew a Cessna 172 into the cliffs above Emerald Lake, in zero visibility weather, killing him.

- In 1980, on June 8, a twenty six year old man from Oregon died when he fell into what is now called “Lower Killer Snow Hole,” by First Falls above Aspen Grove, a part of a snowfield with snow melt running beneath it that thins the snowfield from the bottom up, essentially making an ever thinning snow bridge that hikers mistakenly assume is solid all the way the the ground.

- In 1980, on June 9, a twenty six year old man from Orem died when he crossed the same snowfield as the June 8 victim, and fell into the same killer snow hole; searchers found the body of the Oregon man when looking for the Orem man.

- In 1980, a twenty four year old Brazilian died from a fall in Primrose Cirque while hiking Timp in late October; his companions could not locate him because of darkness.

- In 1982, a twenty nine year old man from Nephi died at Lower Killer Snow Hole when he fell through the snow, dropping into the rushing water and rocks of a snow cavern.

- In 1982, a fourteen year old Orem boy died on July 3 when he fell into what is now called “Upper Killer Snow Hole,” near the waterfall by the upper Primrose Cirque switchbacks, landing in a deep crevice that it was difficult to rappel into to retrieve the body.

- In 1985, a seventeen year old girl died when she slipped and fell down a steep snowfield and over a ledge while hiking with classmates from the Unified Studies group from Orem High School, which was making its way through the Big Provo Cirque area above Sundance when this and another accident happened.

- In 1988, a local thirteen year old Boy Scout from Orem died when he fell at Stewart Falls (Stewart Cascades) while climbing along a rock wall after he and a friend left camp to go hiking.

- In 1990, a twenty two year old BYU student from Centerville died after falling from a cliff near Stewart Falls (Stewart Cascades), where he had gone to pray about marrying a girl.

- In 1993, a fifty year old skier from Florida, who was part of a group skiing in a closed area of Sundance, died when he was buried in an avalanche.

- In 1994, a twenty four year old Lehi man committed suicide above Stewart Falls (Stewart Cascades).

- In 1996, a nineteen year old killed himself near the base of Big Baldy.

- In 1997, a twenty six year old USU student from Logan died while skiing a snowfield on the Timpooneke trail, when he fell and then slid into a crevasse.

- In 1997, a forty one year old Provo man was found dead in Timpanogos Basin, having gone there to meditate and find himself, but ultimately having died of hypothermia.

- In 1998, a man collapsed and died on the Dry Canyon trail, of an apparent heart attack.

- In 2000, a man’s body was found by hikers up Battle Creek Canyon, where he had committed suicide.

- In 2003, an eighteen year old, a nineteen year old, and a twenty year old from Utah County who were snowboarding north of Elk Point, died when a series of avalanches from high above came down the northeast chute and buried six of nine people in the area (a family of four nearby was knocked down by the avalanche’s air blast but was not caught in the snow, and they dug out one victim who was partially buried twice); none of the men were wearing avalanche beacons, the Utah Avalanche Center had issued a rare “extreme danger” warning that afternoon and searchers were limited in the amount of time they could spend in the area (not that it would have mattered at that point), and only one of the bodies was found within days, with the third body not located until the spring, by a rather surprised hiker.

- In 2005, a young man committed suicide near the mouth of Provo Canyon.

- In 2005, a thirty one year old snowshoer with a wife and two daughters in Salt Lake County, died in a slab avalanche above Hidden Lakes; neither he nor a friend who was with him had avalanche beacons, and conditions hindered searchers from reaching the site (not that it would have mattered at that point), and his body was not located until the summer.

- In 2006, a forty one year old man from Russia died when he tried to rescue a three year old girl who was distracted by a snack, and walked off the edge of the Timpanogos Cave trail; she slid to a stop just short of a precipice, but when he tried to reach her he slipped on the shale slope and slid over the edge (two other men eventually reached her and stayed with her until she could be hoisted by helicopter).

- In 2007, an eleven year old Pleasant Grove boy was killed by a black bear that drug him from the tent his family was camping in off Timpooneke Road past the campground; there was food in the tent, and the party that camped there the previous night had left food out.

- In 2010, a fifty eight year old Timpanogos Cave National Monument employee died while doing maintenance on the paved trail to the cave, when he accidentally drove a motorized trail bike off the side of the trail and fell hundreds of feet.

- In 2012, a twenty two year old BYU student from Nevada died when he fell while climbing rock, without gear, at Stewart Falls (Stewart Cascades) while on a church outing.

- In 2016, a fifty five year old woman from South Carolina died while sliding down a zipline at Sundance, reportedly because a wind gust broke a tree top off and she ran into it as it fell.

- In 2018, a thirty six year old man from Orem fell and died while adventuring on his own in the East Peak/Elk Point area; no one knew he had gone to that area, although after he was reported missing and his car was found at Aspen Grove, his body was found a few weeks after he fell.

- In 2020, a seventy two year old Provo man hiking up the Timpanogos Cave trail collapsed and died.

- In 2020, a fifty seven year man from Highland, who was hiking as a Timpanogos Cave National Monument trail volunteer, died of a heart attack near the cave.

- In 2025, an eighty two year old local woman collapsed and died while hiking the Stewart Falls (Stewart Cascades) trail.

Please don’t be next.

Your Choice

Last updated in early 2026 while looking at the bare lower slopes of Timp and wondering what has gone wrong with the winter.